Admiration And Inspiration

Gary Hill

Basically, I'm envious.

These photographers captured the images I wish I had captured.

•Jim Mortram•

Jim Mortram is probably the least well known photographer on this page but, to my mind, he's one of the finest documentary photographers working in the UK today. I first came across Jim in the early 2010s as a fellow member of the now defunct photo sharing site 'PhotoBlur'. It took me seconds to realise that his strikingly honest, bare bones black and white photography was head and shoulders above the usual contributions. I was surprised at the time to learn that he doesn't do this for a living, he'd actually quit art school to be a full time carer for his mother who suffers with severe epilepsy, finding himself socially isolated, and only started out on his photographic journey when he was loaned a camera. His first attempts were captures of his elderly neighbour.

In 2006 he spread his social net wider and started capturing images of people in his hometown of Dereham in the English county of Norfolk, focusing solely on the day to day lives of the people he felt he understood best; the marginalised, the disadvantaged and the socially excluded. All the people whose lives he has chronicled are known to him personally over time and this, I think, is the chemical reagent that makes his images so strong:

".......you’re providing somebody with a paint by numbers canvas. If you don’t provide the context and the testimony, people can fill it in with their own prejudices and make a photograph be anything they choose........That might be okay if it’s fine art but it’s a dereliction of duty if it’s documentary........Some people I can be photographing in the most intense situations within 30 seconds of entering their flat. Others have taken six years to be ready to say they want to do it."

His project, named 'Small Town Inertia', eventually became a blog, a published book, and several exhibitions. His work continues to develop the theme:

"I’m still really pissed about the ignorance – both political and social – of so much pain and suffering.......telling these stories, for me, is a peaceful form of resistance to a very real situation."

•Bert Hardy•

I view poverty as photogenic. I also think that photography needn't and shouldn't deprecate people that find themselves in poverty. This is not (I sincerely hope) a superior cultural attitude on my part, more a valuing of accurate historical documentation. I see Jim Mortram as following in some of the footsteps of Bert Hardy. His images from Gorbals, an inner-city suburb of Glasgow, from 1949-1950, are now considered as important socio-historical data. As he later wrote:

"The streets were slippery with refuse and often with drunken vomit. It was a place of grime and poverty."

Indeed, I've shown Hardy's images to people of my age who have denied that Britain ever experienced such poor standards of living only a few years before they were born (though they often somehow think that the rest of Europe definitely did). Memories can be short and selective and photography is surely the best way to counteract this.

Hardy was a documentary and news photographer from London (labelled a 'professional Cockney') who, although photographing the rich and famous and, as an advertising photographer the things they could buy, was also the very antithesis of a celebrity photographer. As a self-taught photographer for the mass-circulation magazine Picture Post, he had a gift for capturing the gritty streets and no-frill lives of people living through the blitz of WWII and in the poorest districts of both urban and rural post-war Britain. These images always seem natural. Even when looking at the lens (which is uncommon, even in his portraits) the people he photographs never seem alarmed or surprised by his presence. It's as if he's either made himself invisible or become a natural, expected part of the scene. And in a way he was. He came from a working class background himself, from a family with seven children living in two rooms, and he left school at 14 years old. No doubt it also helped that he chose a small 35mm Leica rather than the larger formats more commonly used by press photographers. He died in 1995 aged 82 years.

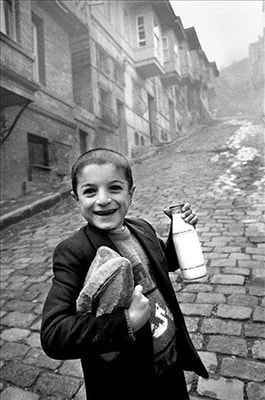

•Ara Güler•

Continuing with the working class theme, I feel a vague sort of distant kinship with Ara Güler. I was introduced to his work during a chance meeting with a professional landscape photographer in a pub in the Scottish Highlands in the early 1990s. I was a novice, having recently bought my first SLR, and was probably boring him with my newly developed prints from a recent trip to Romania. He stopped at one image, a monochrome of a young Romani girl holding a lamb in a sling to her chest, and said it reminded him of the style of Ara Güler. This meant nothing to me at the time so I'm glad I got him to scribble the name down for me.

An Armenian-Turkish documentary, street and portrait photographer, Güler photographed anybody, from heads of state and celebrities to street urchins and every kind of person in between, in both colour and black and white, using his vast array of 50+ cameras, mostly Leicas. I don't have any particular interest in his colour work, nor in his portraits of such diverse characters as Salvador Dali, Mother Teresa, Alfred Hitchcock and Winston Churchill. Nor do I agree with him in his denial of photography as an art form "photographs are not important enough to be hung on walls", he even denied he was a photographer!):

"I am a photojournalist, not a photographer; I certainly am not an artist. I shoot what I see. I don’t do art. I transmit what is natural, what I see to people. That is called photojournalism. A photographer is very different from a photojournalist."

I do agree with Güler, however, in his view that "black and white is in our genes" - well, they seem to be in mine - so I do appreciate his black and white street candids and informal portraits depicting working class mid-20th century Istanbul, which have given him a reputation as 'the eye of Istanbul.'

I was in Istanbul at the end of 2015 and had learned of his coffee shop in the Galatasaray district, and how he was sometimes found there, chatting to the customers. So I went, hoping to thank him for the photographs, shake his hand and tell him of my having accidentally copied his style, maybe even get an autograph. Of course, he wasn't there and I'll never get the chance again, as he died three years later, aged 90 years.

The images chosen here link to a portfolio of black and white shots from Istanbul on Ara Güler's personal website.

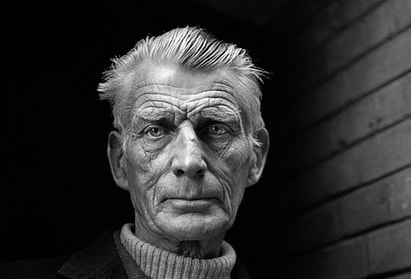

•Jane Bown •

This image of Samuel Beckett (above left) is my favourite portrait, ever. I like everything about it, technically and aesthetically. The story goes that she was either late to the theatre or he left early to avoid her, and she rushed around the back to the stage door where she was lucky to catch camera-shy Beckett exiting. He impatiently allowed her five shots. This was the third attempt and his impatience seems evident, at least to me. Actually, five shots wasn't unusual for her. She got many of her portraits shooting a single roll of film within a quarter of an hour. She even claimed that some of her best portraits were achieved at the first frame:

"I am a single shot photographer. Just one shot, the shot that is right........it's often the first or last shot."

Jane Bown was one of the most respected British portrait photographers of the last century, specialising in photographing famous people for the Observer newspaper, with a preference for famous artists, actors, writers and musicians of all kinds. What makes her stand out from most other great portrait photographers was the intuitive (some might say haphazard) way in which he went about her trade. For example, she started out using a Rolleiflex, swapped it for a Pentax in the 1960s then, in the early 1970s, to several Olympus OM1s, none of which were purchased new. She used either a 50mm or 85mm lens set to 1/60th sec. and f2.8 and, apparently, would never shoot at 1/1000 sec., even on a sunny day. She eschewed what the light meter told her and used only available light and occasionally a 150 watt bulb, which she always carried with her to fit in any available desk lamp. Furthermore, she would arrive at a portrait session carrying her meagre kit in a wicker shopping basket.

Despite her familiarity with the rich and famous, in my opinion, some of her best images were candids of ordinary folk going about their lives. I've included two below. These are also in black and white because, like me, she thought that: "Colour is too noisy, the eye doesn’t know where to rest."

In retirement she donated her archives to the Guardian News & Media Archive and died aged 89 years in 2014 after spending "my whole life worrying about time and light." She had no personal website but a good introduction to further work is an article in the Guardian, 'Jane Bown: A Life In Pictures'.

'Admiration & Inspiration'. Written content © Gary Hill 2023. All rights reserved. Not in public domain. If you wish to use my work for anything other than legal 'fair use' (i.e., non-profit educational or scholarly research or critique purposes) please contact me for permission first.