Once A Not So Jolly Swagman: The Story Of Joseph Jenkins

Gary Hill

While researching for my essay 'Destined to Fail: The Ministry of William Meirion Evans', I happened upon the story of Joseph Jenkins, another fascinating and strong-minded Welshman who had immigrated to Australia in the 19th century. Any similarity between the two men ends there, however. It is hard to imagine two individuals sharing a common cultural heritage who could be any more different. William Evans was from North Wales, Joseph Jenkins was a South Walian; Evans was a miner and later a church minister, Jenkins a farmer and later a street cleaner; Evans was a dedicated family man while Jenkins turned his back on his family for a quarter of a century; they belonged to two very different non-conformist Christian sects; they wrote their memoirs in different languages. Although they were unaware of each other while living in Wales their paths would have crossed on quite a number of occasions in the Australian colony of Victoria where they both, in their own very different ways, played important roles in the history of the then fledgling nation of Australia.

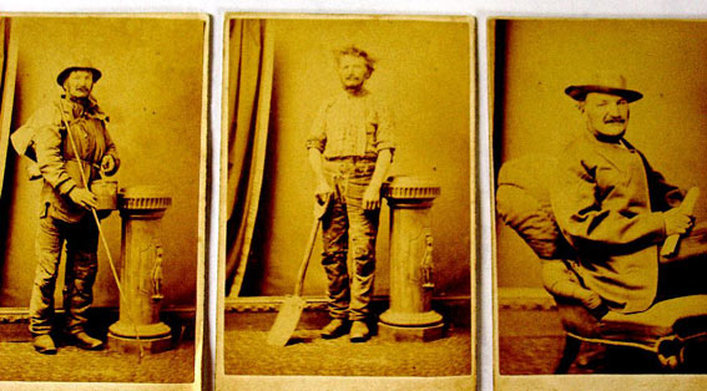

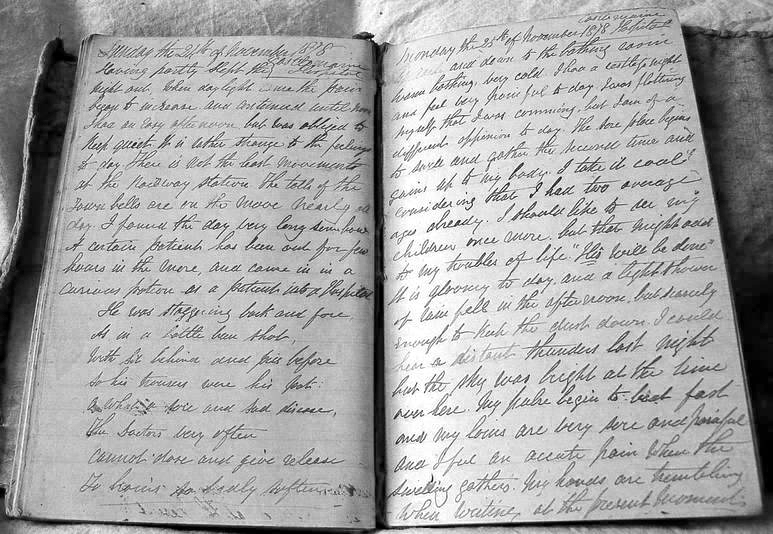

Joseph Jenkins was an extraordinary and enigmatic man. A successful farmer in Wales, he abandoned his family and farm to become a swagman (similar to the American hobo) in Australia. This decision alone makes an interesting story but what set Joseph Jenkins apart from the hordes of other swagmen was that he wrote, in a time when the majority of his contemporaries were largely illiterate and unable to write even a simple letter, a detailed diary every day for 58 years, including the 25 years he spent living in Australia as an itinerant worker. What is more, he wrote nearly every word in English, his second language, which he had largely taught himself. He differed too from other authors who had lived itinerant lives. Unlike Jack Black for example, Joseph was scrupulously honest and, unlike John Steinbeck, he never achieved literary recognition during his lifetime.

Joseph’s diaries are primarily a reflective view of his daily life experiences and his work, rather than stories. As such he has arguably left us with the most comprehensive chronicle of daily life from the perspective of a working man ever to be found in either Britain or it’s colonies. But Joseph Jenkins proved to be much more than a chronicler of his daily life. Not only was he an astute social commentator but he possessed an appreciable intellect, ably demonstrated by his writings on a variety of subjects ranging from literature, philosophy, theology, local politics and world affairs. In addition to his dairies, he wrote award-winning poetry in the Welsh language.

Born on February 27th 1818 at Blaenplwyf farm (not to be confused with the village of the same name), in the parish of Llanfihangel Ystrad, Cardiganshire (now part of the modern county of Ceredigion), Joseph Jenkins was the son of a farming couple, Jenkin and Elinor Jenkins (née Davies). He came from a family with literary leanings. His mother was the niece of Dafydd Dafis (1745-1827), the church minister and poet who had translated Thomas Gray's famous poem ‘Elegy In A Country Churchyard’ into Welsh and his brother John also achieved some fame within Wales as a poet. The Jenkins’ had twelve children in all with Joseph being the fourth born. The oldest, a boy named Griffith died in infancy and according to the census of 1841 the next two eldest, Margaret and another Griffith had left home, leaving Joseph as the oldest of the remaining nine children living at home. However, it is known that he had recently returned from living on his aunt’s farm, Clwtypatrwn in nearby Llanfair as it was there, on New Year's Day in 1839, that he began the first of his diaries, beginning with barely legible one line statements.

Unusually at a time before schooling was universally available in Wales, Joseph was educated privately for a short while and, probably because Elinor came from a family with some members influenced by Unitarianism, he then attended a small Unitarian church school in the village of Cribyn, which necessitated him walking sixteen kilometres there and back each day. Although he later described his education as only “two quarters of schooling”, albeit by a "teacher without parallel", his good fortune in being able to access at least some formal education undoubtedly played a significant part in his lifelong interest in literature, especially poetry, philosophy and current affairs.

Nonetheless, his lack of more complete formal education was a source of much regret throughout his life and he wrote on more than a few occasions of how he was “doomed” and “cursed” from birth and that “even in the womb of my mother I was born under an unfortunate star" (he was born with a hare-lip) and "I feel my life has been filled and covered with darkness and sadness" and further, "save me from the curse of myself.'' Not surprisingly then, he was considered by many as a cantankerous, melancholy and introspective man, prone to profound mood swings.

A fluent native Welsh speaker (and later writer), he was also taught some spoken and written English at school and, typical of his thirst for knowledge and quest for self-improvement, he chose to write his daily diary, almost always using a quill pen and ink, entirely in English, in a lifelong effort to master the language. His obvious enthusiasm for this endeavour alone, performed after hard manual labour for up to sixteen hours a day and often by candlelight, seems at odds with the generally depressing and deprecating view he had of himself. He described his diary as “this long, lonely affair with myself” but added “my diary saves my mind but poetry feeds my soul.” Seemingly more important than either his family or his farm, maintaining his diary does seem to have been the rock which gave him psychological stability. As his biographer Bethan Phillips observes “The diaries reveal him as a man seeking to exorcise his own demons by attempting to escape from them”.

His poetry has been described as “consistent if not outstanding”. However, during the 25 years he lived in Australia he regularly attended the St. David’s Day Eisteddfod (St. David being the patron saint of Wales) at Ballarat, organised by William Meirion Evans. Again, competing at this Welsh cultural gathering seemed to be important to him as on each occasion he walked the many kilometres to get there. Writing under the bardic pen-name Amnon II he won the chair for poetry on a still unparalleled thirteen consecutive occasions (1870-1882). In the fourteenth year he didn't compete as he had missed the deadline for submission. Joseph Jenkins specialised in ‘englyn’, a form of poetry peculiar to Welsh and the closely related Cornish language which employs strict quantitative metre involving the counting of syllables, along with rigid patterns of rhyme and half rhyme. True to his melancholic nature the subject matter of his englynion were more often than not the deaths of people he had known.

His sparse education gave him more than an enthusiasm for literary endeavours, however. He was to remain Unitarian in outlook for the whole of his life. Unitarianism differs markedly from the teachings of the then-established Anglican Church in Wales and the then far more popular Welsh Baptist and Methodist chapels in a number of ways. Briefly, Unitarians hold to a strict monotheistic view and so are strongly opposed to the Trinitarian theology of the majority of Christianity. They thus do not accept that Jesus was born God-incarnate but rather that he acted as many other human prophets had done. Unitarians accept neither the concept of original sin nor the inerrant nature of the Bible and state that no one religion can legitimately claim to hold the entirety of religious truth. Not surprisingly, they also tend to play down the role of faith and place value on reason and rational thought. Technically, it was illegal in both England and Wales to question the view that the Trinity was not theologically robust or to even preach Unitarianism until the Doctrine of the Trinity Act was passed 1813. Effectively, until then, most Unitarian-minded individuals kept quiet regarding their religious beliefs. A good example of this was Isaac Newton, who we now know, via his personal writings, held to strongly anti-Trinitarian views and would certainly have been considered to have been an heretic had they become public.

It is ironic then that three stalwarts of the strict fundamental Methodist cause in Wales have prior connections with his birthplace at Blaenplwf farm. First there was the fiery preacher and hymn writer Daniel Rowland (1713–1790) who lived at Blaenplwyf for a time. Second was the Independent Methodist preacher Thomas Grey (1733-1810) who married Letitia, widow of Theophilous Jones, a past owner of Blaenplwf. Third was the first romantic poet to write in Welsh and chief hymn writer of the Methodist awakening in Wales, William Williams Pantycelyn (1717–1791, also thought to have lived at Blaenplwyf).

During Joseph’s lifetime, the various chapel cultures in both Wales and Australia were plagued by seemingly endless disagreements which mostly concerned the way in which the institutions were governed. While Calvinistic Methodists, for example, had elected church governments, the Independent Methodists advocated majority leadership by the entire congregation. These differences were not purely political, however, ultimately reflecting doctrinal and theological differences concerned with each denomination’s interpretation of how an individual may relate with God and the strength of the mediating role of the chapel in that relationship. The conflicts could be particularly vexatious, often causing irreparable rifts within families, whole villages and towns. Unitarianism has always been a relatively minor sect of Christianity with far fewer chapels than those of the Baptists and Methodists and so Joseph Jenkins often found himself forced to attend other services. He remained unimpressed by their internecine warfare, however, and his responses were typically Unitarian:

“Four miles away [in Castlemaine, in the Australian colony of Victoria] there are three chapels belonging to different denominations. They are so close together that they are forever quarrelling. Mrs Lewis and her son walked to chapel to listen to a Welsh sermon, and I walked into the bush to meet my God”

“I attended three church services today, and listened to two sermons. It would have been better had I stayed in my cottage and re-read the ‘Sermon on The Mount’”.

On July 31st 1846 aged 28 years, Joseph married his 18-year old second cousin Elisabeth (Betty) Evans in Capel Ystrad. She was the daughter of Jenkin and Margaret Evans (née Philips), relatively wealthy farmers of Tŷ Nant, Ciliau Aeron. Initially, Elisabeth remained living with her parents but two years later the couple moved, with their first child, also named Jenkin, to Trecefel, a 74 hectare farm on the south-eastern outskirts of the small town of Tregaron. The five bedroom farmhouse still stands and is considered to have architectural historical interest, being named a Grade II listed building. Trecefel was leased from the Rev. Latimer Jones, the Vicar of St Peter's Church in the county town of Carmarthen.

It is important to recognise the distinction in Welsh society between chapel and the then established church. The Anglican-based ‘Church in Wales’ had long been associated with cultural 'Englishness' and 'landlordism' and catered largely to the 'aspiring' Welsh who spoke English by choice, even when their own language could be fully understood and fluently spoken. In other words, attending church, rather than chapel, was a prime social indicator of influence and wealth. That Joseph Jenkins would lease a farm from a member of the clergy of the Anglican church would not then be unusual. What was unusual, for a native Welsh-speaking, Unitarian tenant farmer, was the way in which he was gradually accepted by the landowning community. Trecefel abounded with game and Joseph was an expert marksman. As a result of both his shooting prowess and ability to converse fluently and knowledgably in English he found himself increasingly invited to take part in hunts organised by the landowning class, often followed by formal dinners.

Hence Joseph found himself becoming slowly but surely becoming ostracised from his peers, culminating in his support for Tory-voting landowners despite their generally oppressive attitude toward tenant-farmers in many parts of Wales. His political stance was in stark contrast to most of his contemporaries who tended to actively promote Liberal Party candidates with more generous attitudes on issues surrounding land ownership. As a result Joseph Jenkins lost a number of close friends and his standing in the community generally suffered. It probably did not help his cause that, in the absence of a Unitarian place of worship close to Trecefel and in need of a spiritual anchor in his life, he became warden at St Caron's Anglican parish church in Tregaron, where he was responsible for the upkeep of the cemetery and buildings. He also arbitrated at Anglican church courts in Carmarthen.

Joseph Jenkins proved to be an enthusiastic and successful farmer at Trecefel. He invested a substantial amount of money in the farm and won numerous prizes at agricultural shows with his cattle fetching premium prices at market. In 1851 Trecefel was awarded best farm in the county and ten years later he was asked to judge the same competition. The census of 1861 indicates that he was employing three full-time labourers, a rare occurrence for a tenanted family farm.

Critical of much of the farming practice at the time he had innovative ideas on sustainable agriculture and wrote several articles for farming journals in which he advocated a rotation system for growing crops, harvesting hay while young and, one farming technique he was fond of promoting throughout his life, fertilising fields with manure (there is a modern-day proponent of using manure in agriculture who is also named Joseph Jenkins, the American author of the ‘The Humanure Handbook: A Guide To Composting Human Manure'). Joseph Jenkins the elder championed the use of clover and lucerne crops to provide fodder during severe winters. He also spoke against deep ploughing in order to maintain the integrity of the soil and favoured thorough harrowing.

He was actively involved in his community, as a parish constable, a magistrate and a member of the Board of Guardians, responsible for the welfare of orphans and the insane. No doubt inspired by his own short experience, he was also instrumental in bringing primary school education to that part of Wales. His English writing skills were often in demand by friends and neighbours for the drawing up of legal documents and his Welsh writing ability was often requested to prepare eulogies for funerals.

Then, on December 8th 1868, aged 51 years, and apparently without any warning, his family woke to find him gone. Joseph Jenkins left his home and family for Aberystwyth, passing a brother’s house on the way, and caught a train to Liverpool. His only funds were the rent money for the farm. There he boarded the cargo ship ‘Eurynome’, setting sail for Melbourne, via Brazil, in the Australian colony of Victoria. It appears that on this occasion his fate was not as doomed as he had so often thought for fourteen years later, while returning to the UK from Australia, the ‘Eurynome’ was lost at sea with all hands.

Why he took this course of action is uncertain and the subject of much speculation. He does not address his reasons explicitly in his diaries but does say that “it was not my fault I absented myself from home”. He may have been, at least partly, inspired by two of his brothers, both of whom emigrated to Bangor, Wisconsin, where there was a sizable Welsh émigré population. David Jenkins (1829-1871) had left Wales in 1852 followed four years later by Timothy Jenkins (1837-1882). The two brothers enjoyed mixed fortunes. David became a mill-owner and Justice of the Peace who was wealthy enough to retire before his 40th birthday. He married an artist named Mary Williams who hailed from Massachusetts. Their marriage did not last long for soon after returning from a visit to Wales he died aged 41 years of a 'pulmonary affection', according to his death certificate. His wife survived him by some 59 years. Timothy too experienced tragedy. He farmed 32 hectares, having decided against joining his brother in the mill venture. He married a Mary Jones, and they had seven children only four of whom survived. Three were named Mary Anne; the first, born in December 1862 died less than two months of age, the second, born in 1864, died fifteen months later. Only the third, born in 1866 lived to adulthood.

The most prominently cited reason for Joseph leaving is the breakdown of his marriage, exacerbated by his excessive drinking (though he generally abstained from alcohol while in Australia, taking the Templar’s oath of abstinence in both 1873 and 1890, even avoiding medicines containing alcohol), neglect of the farm and subsequent reliance on financial aid from Betty's father. This, in turn, appears to have been the aftermath of the death of their eldest son Jenkin at only 17 years old from tuberculosis in 1863. There has been some conjecture that Betty blamed Jenkins' death on Joseph, after he allegedly made him work long hours outside through the winter months. There were stories also of Betty’s infidelity. However, the situation is likely far more complex and his decision to leave may have resulted from a culmination of events. In his diary entry of May 26th 1868 Joseph writes of a prolonged assault, lasting for two hours, by Betty, his now eldest son Lewis, his eldest daughters Elinor and Margaret and their maid:

“. . . my ribs and breastbone were fractured . . . I have an ugly black eye with about a dozen other different wounds”.

However, there is no independent evidence of this assault, or of Betty’s alleged infidelity, though we know that he expressed doubt that he was the father of their ninth child, born that same year. This doubt never seems to have left him; over 20 years later, when recalling a dream he had the night before, he describes Betty as a "fornicator." Interestingly, although he rarely wrote of Betty after leaving, one volume of his diary was found to include a newspaper cutting concerning a man who had left home because of his nagging wife. A second possible reason for leaving was the loss of prestige following his ill-advised support for the landowners in the General Election of 1868 (including the Tory candidate for Cardiganshire) which had taken place only six days before he set sail. A year earlier, the Second Reform Act had enfranchised working men. Across Wales, many of the sitting members of Parliament from powerful landowning families lost their seats and 23 Liberals were elected compared to a mere 10 Conservatives, although 24 of the 33 Members of Parliament remained landowners. Cardiganshire narrowly returned the Liberal Evan Richards with a majority of 156 and, in retaliation, local Tory landowners evicted 30 tenant farmers and their families that were known to have voted for him. In response the various chapels put aside their differences and quickly organised a collection, raising £20,000 as a compensation fund for the evicted farmers. Obviously, had Joseph Jenkins stayed in this political climate he would have been persona non grata.

It is possible also, paradoxically, that Joseph Jenkins was thinking of his family, as he had arranged legal provision for his family to stay on at the farm before he left. Joseph and Betty had eight surviving children. Their second born, Lewis, was now 19 years old, Margaret was 17 years old, Elinor 15 years old, Mary 13 years old, Jane 10 years old, Tom Jo 6 years old, Anne 4 years old and John David less than a year old. Agriculture in Wales was in the doldrums in 1868 and Joseph may have thought that having one less mouth to feed, and a working farm to hand over to Lewis may have been preferable to him battling on at Trecefel with his and Betty’s personal problems and increasing estrangement. He also suggests that he had notions of making his fortune in the goldmines of Victoria and returning to Wales as a wealthy man, though he left it a decade late for the height of the gold boom. Tragically, however, Lewis did not take over the farm as he died, aged just 20 years, less than a year after Joseph had departed Wales.

The outbound voyage was not a happy one for Joseph. Apart from bearing the guilt of leaving his family he writes of bearing the brunt of jokes and ridicule among the other, dozen or so English passengers, for his obvious ‘Welshness’. He showed particular deference to the captain, however. It was a condition of travel that diaries written aboard the ship could be examined, lest they portray the shipping company in an unfavourable light; "Anyone found writing against him will be guilty of High Treason!"

According to the shipping register The ‘Eurynome’ finally docked in Port Melbourne three months later on March 12th 1869, though Joseph incorrectly gives the date of March 22nd in his diary. His funds all spent, he then walked along with a number of other swagmen, 120 km north-west to the goldfields of Castlemaine, where there was a large community of Welsh-speaking miners and where he offered his services as a farm labourer. Unable to find agricultural work due to a prolonged drought, he then walked to Taradale and Chewton before returning to Castlemaine, commenting that he meets at least fifteen swagman every hour when on the road, and that for every labourer who is able to find work, five more go unemployed. Unfortunately some of the details of this period are lost; his diaries dated April to September 1869 were stolen, leading Jenkins to have a letter published in the 'Australasian' newspaper on 18th November 1869, entitled 'Pity the Swagman' in which he derided his fellow swagmen as "beggars, loafers and vagabonds." Later, in 1874, he had a pair of new boots stolen by another swagman.

He estimated that, in the late 1800s, there were regularly around 200,000 swagmen in Australia looking for work out of a population of approximately 1.7 million. Such a figure is probably an exaggeration. Nevertheless, one of those swagmen had been born in London to a Welsh-speaking family and was a fluent Welsh speaker himself. For two years he walked around the colonies of Queensland and New South Wales willing to take on any work offered and worked 15-hour days as a cook, sheep-shearer and railway labourer. Eventually he moved to Sydney and, never forgetting his working roots, became involved in the Labor Party. He was eventually elected to the New South Wales parliament, serving seven years and, after the colonies federated in 1901, he was elected to the Australian parliament. Billy Hughes subsequently served as Australian Prime Minister for eight years from 1915-1923. He still remains the longest serving member of parliament in Australia. That an ex-swagman could become Prime Minister at all is a clear example of the opportunities available in Australia at that time and of the difference in social attitudes between the UK and Australia.

Joseph Jenkins was probably at least as intellectually equipped as Billy Hughes to succeed in Australian society but he was no longer as socially ambitious as he had been in Wales. In any case, he preferred the country to the city and remained within 30-40 km of Castlemaine for at least 20 of the 25 years he spent in Australia. What follows is a potted history of his life in the Australian colony of Victoria and some of his diary extracts, starting in March 1869:

“Unbearably hot with the temperature registering 118°F (48°C) I came upon a large park with some 22,000 halve (sic) starved sheep, devoid of grass and water. Dreadful stench from the carcasses of dead sheep. I had a contest with a large snake on the road......There is nothing but red sand and dust to be seen for miles. The flies are troublesome; my face is swollen from mosquito bites. The cattle are bellowing for water and dying by the score; the stench is unbearable. The land looks more like scorched hearths than green fields..... a large sow brought a lame cow to the ground and began to eat it alive.....Was awakened by a traveller. He had an axe and a dog. He made to steal my bedclothes. We fought, I overcome him”.

In May 1869, he arrived at Smeaton, where he was to find his first work. For the next quarter century he describes finding precarious seasonal and short term employment felling trees, splitting timber, carting hay, ploughing fields, binding and stacking wheat, planting and picking potatoes and carrots, building sheds, hanging gates, carting rubbish, digging unsuccessfully for gold and maintaining drains, all the while walking long distances from town to town and carrying a pack weighing more than 30 kg. As each year went by this pack would increase in weight due to each additional volume of his diary.

It is fair to say he was generally unimpressed by both the farm owners and the farming methods in Victoria, the general attitude of the inhabitants toward and the general economic conditions for farm labourers. Although he observed Australian farming to be more mechanised than Welsh farming, he noted there were:

“Thousands of acres of fertile land around Smeaton, but poorly farmed. The farmers consider it too expensive to cart farmyard manure to the land, so they pay 9 shillings per hundredweight for potatoes which they are unable to grow. No land is properly cultivated around here except the townspeople’s gardens”.

The waste of good manure was something he commented on often, as was the failure to cut winter feed for stock. From February 1870:

“The dust drifts like snow. Travellers have to lie on the ground to avoid thick clouds”

And in May, 1871:

“The two qualifications required of the young are dancing and piano-playing, not milking and butter- or cheese-making. Smeaton district, once considered the garden of Victoria, is now a ruinous area from continued exhaustion of the land. The farms are over-run by weeds. There are numerous deserted homesteads. Landlords are letting their land for 5 shillings an acre to tenants who have no capital to improve it. Two-thirds of the farmers are unable to pay their rates which only amount to 1shilling in the pound.......hundreds of swagmen pass by looking for work”.

The problem, as he saw it, was that if farmers were liable to pay tax, they would be more inclined to increase productivity, hire workers throughout the year, and better prepare their land for drought and bushfire. Between December 1872 and February 1873, he writes of his work on a farm at Coghill’s Creek owned by a John Hopkins and a John Hawkins. He was initially paid 4d an hour working alone, later reduced to 2d when working as part of an eighteen man threshing team. Again, he is unimpressed with farm management techniques:

“The land is poorly managed. Land must be exceedingly rich to produce 15 to 24 crops in succession and without farmyard manure. It will be more difficult to bring it under proper cultivation than when it was first cleared of scrub. The parcels of land are too large and their management is undermanned. Relations between farmers and labourers are bad”.

And echoing William Meirion Evans’s moral view of the Australian labourer:

“This country’s soil and its climate cannot be surpassed by any country, but the law and the lawless cannot be so classed. So wanting are high principles, humanity and morals, that people from all classes of society hold that no honest man should set foot in Australia. I would not complain of the labourer’s wages, if he were respected and be constantly employed. Now, a labourer is not employed for longer than 12 to 17 weeks of the year. Consequently the land is neglected and exhausted”.

In stark contrast to his previous attitude to land ownership in Wales he later writes:

“Presently, one man is allowed to hold a million acres of land with good surface soil without obligation to employ a single labourer, while the same land is neither rated nor taxed. On the other hand, the small farmer has to pay a tax of 1shilling in the pound to support public roads, although there are no roads serving the squatters”.

In March 1873 he tells of coming across three men. One was offering the other two work sewing the sacks used to store corn. They both refused:

“I was asked if I could sew bags, “Yes Sir” Had I needles? “Yes Sir”. “Come with me and get your breakfast”. The work was finished by lunch, having repaired more than 200 sacks. No more work, but good tucker (food) and wage from the kindest farmer so far met in the country. They are two brothers, T & J Meredith, from Montgomeryshire in North Wales”

In contrast to the Meredith brothers, from April to July 1873, he laboured for Thomas McMurray at Glendanal near Clunes, describing him as “a scoundral, swindler and tyrant.” He similarly describes a farm owned by a William Clarke, located between Clunes and Talbot, as “the most miserable place I have ever worked at”, yet leaving there only because he contracted diptheria, resulting in his spending forty days in Maryborough Hospital, the first of three stints of hospitalisation in Australia. This experience did not stop him from working there again, a couple of years later however.

The period 1875 to 1878 was one of more steady employment. He starts his 1875 recollections by recounting how he had to concoct his own book as he had forgotten to buy one and the shops were closed on New Years Day. In early 1875 he moved away from his usual locality and travelled to Geelong where he was employed as a farm labourer for fourteen months straight, until April, 1876 at ‘Spray Farm’ on the Bellarine Peninsula. There, he reports being treated with kindness in beautiful surroundings and appears much happier writing “O what a glorious country this is! How I wish I could acquire twenty acres....to farm it on my own”. Unfortunately, the farm became bankrupt and Jenkins again needed to look for work. He found some on William Wescott’s orchard and potato farm near Bungaree, where he stayed for two years, leaving in September 1878.

In January, 1880, he worked harvesting “an excellent oat crop” for a Mr J. Glendinning of Summerset Farm. Again, he complains of the attitude of the farmers toward their workers, an issue he eventually campaigned for by writing to several local newspapers:

“On this Sunday I climbed on to a hill, 500 feet (152 metres) high, and surveyed the countryside. It was a very pleasing sight with the paddocks packed with stooks of precious grain, gathered through the assiduous labour of the swagman, whom they variously abuse and call loafer, vagabond, and sundowner.”

In August 1882, with his ability to walk long distances diminishing and realising that he was getting too old for an itinerant lifestyle, he took advantage of a 'miner's right'. On payment of £1, he was entitled to one acre of land, a roadway and a water spring. He built himself a timber hut and vegetable garden that he named Ant’s Mole Cottage, in Ravenswood, 12 km north-east of Walmer and 13 km from the town of Maldon. He writes of his joy living here among the birds and small animals. Nevertheless, his troubles remained. He supplied seven tons of timber from the trees on his land for which he was not paid and someone attempted (unsuccessfully) to legally seize his land under an amendment to the Land Rights Act. On at least one occasion his hut was broken into and his diaries scattered around on the ground outside the hut, resulting in them becoming wet and suffering mould damage. His hut was eventually burned by, according to him, a group of Irishmen. Having received no help from the authorities, he later confronted them armed with a revolver. He rebuilt his hut, but later, during the depression years of the early 1890s his lodgings were again burgled a number of times again. He details the lack of effort on the part of the authorities to deal with such lawlessness and their corrupt practices:

“...an Irish farmer named Michael Owen was charged with assault on a lady, when he bit her thumb, almost amputating it. He was acquitted on payment of expenses. At the same court, three youths were charged with taking ten potatoes which they had cooked directly to appease their hunger. They were committed to jail for three months. Michael Owen is a good customer at the provision store owned by the senior magistrate”.

“No less than five Justices of the Peace were summoned last week for cattle stealing, drunkenness, rioting, and other breaches of the law, but they got away from it when judged by their equals.”

In contrast to many of the Christian European population in Australia, Joseph Jenkins had no problems in his dealings with the indigenous population nor with non-European immigrants. He especially admired their sense of kinship and their knowledge of the environment and deplored the way they were treated. Three are numerous examples of his attitude scattered throughout his diaries and a few are outlined here. First from August, 1873:

“When a native discovers a (bee) hive he invites the neighbours to partake of the honey, but when a white Christian discovers it, he keeps the produce for himself.”

In July 1874, when Joseph Jenkins was a diptheria patient in Maryborough Hospital he wrote of the treatment of a fellow patient, an aboriginal man. Although he considered him to have been treated kindly during his "awful illness", he was appalled with the manner the body was treated after his death:

"No more heed or notice taken of his death than if he was a common fly or moth."

His diary entry was accompanied by a poem written in the man's honour. Next, in his diary entry of 17th May 1871, he protests at the recent census in which Aboriginals and Chinese were counted separately to the European-derived population. In March 1884, speaking of the farmers who refused to fertilise their crops with manure, he had this to say:

"Their land is not half the value now as to what is was when they bought from the thieves who stole from the natives."

Finally, from 22nd July 1887 he befriends an indigenous Australian named Equinhup, otherwise known as ‘Tom Clark’:

“I met an Aborigine. He seemed half starved. I took him into my cottage and invited him to share a meal with me. I shared my blankets with him during the night. A few men in the colony own over a million acres of rich land which was barbarously taken from the Aborigines. The majority held it as of right and even a Christian obligation to be rid of all the Aborigines. In the name of everything – whence came such authority?"

The following day Joseph Jenkins gave him nearly £1. He also authored a letter dated 28th July 1887 addressed to the Railway Commissioners on Equinhup’s behalf, in which he petitioned them for the loss of his tribal land:

"As I am the last of the Aboriginal tribe in this part. So I do humbly wish you to compare the title deeds. I had mine from the Author of Nature, and the land under all the railways is titled by the white man’s lawyers, bush man, bush manners."

Nor, as a Cymro (Welshman), did he consider that he was alone in his sentiments, for in January 1886 he had this to say:

“All Nationalists in this colony stick together selfishly. The Welsh are quite to the contrary. They do not heed a man’s colour, or his nationality as long as he acts straightforwardly. I do believe that they prove the best colonists of any nation”.

it is fair to say, though. that Joseph Jenkins was no liberal, in the sense we would use the term today. Despite his striving for a good Christian life and concern the hard-working man and the native Australian, he could not bring himself to treat women as equals. As he wrote in December 1887:

"women suffrage will turn this world upside down!!"

He was equally unimpressed with his own suffrage, however, although for different reasons. In May 1877 he had described his own right to vote as a "useless bother" and didn't bother to vote as he thought the result was a foregone conclusion. Three years later he refused to vote again "as it is considered that my friends are certain of an overwhelming majority." Nevertheless, the sentiment did not stop him from writing a letter to his local newspaper. 'The Leader' on 15th February stating his political opinion.

Although Joseph Jenkins let little get in his way of earning a living he suffered ill-health and injury with regularity and had particular preoccupations with his rheumatism and his teeth. While in Wales he had written, “I abused my teeth badly when I was young through cracking nuts which grew plentifully on the farm”. Then at 57 years old, “toothache has plagued me off and on for weeks; it disturbs my sleep”. At 60 years of age he listed his complaints as "toothache, rheumatism, sore eyes’ – sandy blight, caused by flies – ‘whitlow on my finger, and abscess in my armpit."

In September 1874 the rheumatism in his hands was so bad he had to make his diary entries with a pencil in his mouth. In 1878, a piece of white quartz flew with some force into his right hand and seriously damaged two fingers. Despite medical advice to have them amputated he bound them together and spent months in severe pain, especially when writing. That same year he went into more detail about his teeth:

“Toothache is harassing me. I am thankful, however, that it is one-sided, and I am able to masticate my food on the other side. I realize that I would not be grateful for the freedom from pain on the one side, had I no pain on the other side…. My teeth are decaying fast”

In December 1883, he received a complete set of false teeth, but they appear to have been less than satisfactory as he noted three years later that he required:

“an hour to cook a meal and eat it, is too short a time for an aged man whose grinders are not sharp-edged...........for breakfast nowadays I have ‘pap’, which is boiled milk and flour, to which is added two tablespoonfuls of sugar and a pinch of cayenne pepper. For dinner I have cold tea with bread and cheese or meat, and mutton broth to which I add bread and meat, for supper”.

Aged 73 years he wrote:

“For my dinner today I had toasted-bread and honey with cold tea. It suited my blunt and rotten grinders”.

In September 1884, he successfully tendered to dig a drain for Maldon Town Council. Located 20 km north of Castlemaine, Maldon had experienced a rapid growth in population due to the nearby quartz mines at Tarrangower Fields. The following month he won a similar contract to clear 600 metres of road, located five kilometres from his hut. A third contract had him road-clearing for Maldon Council, from August to October 1885. However, he still had to walk to and from work each day, which he found increasingly difficult and eventually he found it too much for him and moved to a rented stable on a nearer property. In December 1885 he bid for a permanent contract to clean the water channels running down the sides of the streets in Maldon on a daily basis and to keep the footpaths in repair. His tender of 3 shillings and 4d a day, without board and lodgings, was accepted. He now writes of removing dead dogs and rampant weeds and for the first time he is able to buy a small cottage on wasteland and afford good quality hardbound books for his diaries as well as a steel pen, which he soon discarded as "not equal to the old quill for me".

He befriended a local baker George MacArthur, who had immigrated from Scotland in 1852, aged 10 years. MacArthur was a keen book and coin collector who allowed friends access to his book collection, described by Jenkins as "a Library of poetical and philosophical books of the best type." On 28th November 1886 he tells us that he had finished reading Charles Dickens’ 'David Copperfield' and had inserted his own favourable review in the book before returning it to the library. On his death in 1903, MacArthur bequeathed his entire library of 2,500 books to the University of Melbourne, then representing 10% of their entire collection.

At last he appears to have found some sense of peace and in 1887 writes:

“I have never been so contented in the pursuit of my work......It is my sincere opinion that it is sinning against nature that brings disappointment, while to be in unity with it in doing good, brings lasting bliss”.

Then the following year:

“The floods have left over twenty tons of mud and gravel to cart away from the gutters. I do it with ease. Nothing pleases me better than work when I am able to do it without undue tiredness”.

Nevertheless he also found cause to complain. From January 1888:

“I find it best not to make my bed in the morning.....for at bed-time in the evening I may find a black or tiger snake coiled between the blankets.......The clerk of works to the council should be a trained engineer, but ours is only a weaver from the north of Scotland who has weaved himself into the job through influence”.

He held his street cleaning job for nine years, despite his doctor advising him against working, and notes that there were enough Welshmen living in the town that he could sometimes get through a whole day speaking only Welsh rather than English. Despite having mastered the English language, Jenkins had always preferred to speak in Welsh. He started to take a greater interest in events in Wales. He had kept in sporadic touch with his daughters and they sent him copies of two local newspapers, the ‘Cambrian News’ and the ‘Aberystwyth Observer’. It was in one of these mailings that he had learned of the death of his eldest daughter, Margaret aged 32 years, in April 1883. Sometimes, when he could afford it, he sent them a little money. He became sympathetic to William Meirion Evans' fight for ‘Yr Achos Cymraeg’ (the preservation of the Welsh language in Australia) and, echoing the clergyman’s sentiments, wrote despairingly in March 1889:

“The Welsh people in Australia show great indifference to honouring their national day, and to keeping up their language”.

Twelve years earlier he had written:

“The Eisteddfod in Ballarat on next St David’s Day is to be more of a concert where singing takes the place of composition. I do not think that singing alone is of any advantage to keep up the language of the Ancient Britons. I cannot imagine what the patrons of the Eisteddfod Fawr Caerffyrddin would say to parading this concert as an Eisteddfod” (ironically writing in English).

Eventually, he found the Welsh community dying or moving away from Maldon. He was in rapidly failing health and had become an object of fun for the local children, the "the reckless governors of this place" as he called them. He had developed a fear of dying in Australia, never having seen Wales again and especially not his grandchildren. So he decided to scrape together as much money as he could and return to Wales. It is also likely that he could see an end to his full-time position as the Maldon street cleaner. His appointment had coincided with a decline in output from the quartz mines and the population of the town had reduced by about 70% in the previous 20 years. He caught the train from Maldon to Melbourne on November 23rd 1894 in time to catch the departure of the SS Ophir two days later. He notes that his fare was £26 15s 6d and commenting on the size of the vessel writes, "it is a wonder to me that it would move".

Arriving at Tilbury Dock, England on January 5th 1895 he then completed his journey overland, returning to Trecefel in March 1895. Tom Jo, only eight years old when Joseph had departed, was still living at home and had taken over the running of the farm. Although Betty did take him back into her home she never forgave him for leaving his family and they were to remain forever estranged. Once again, Joseph started drinking. He died at Trecefel, following a long illness, on September 26th 1898 aged 80 years. He was buried, according to his wishes, at the nearest Unitarian chapel, Capel Y Groes, at Llanwnen, five km from Lampeter. Betty later moved to Joseph’s birthplace at Blaenplwyf and died there aged 91 years in 1919. Tom Jo remained farming at Trecefel until his own death in 1942, aged 80 years.

Six years after Joseph’s death some of his poetry was published. Joseph’s brother, John Jenkins (1820–1894), a farmer living in Bronnant, 10 km north-west of Tregaron, on the road to Aberystwyth, was a poet also, writing under the bardic name Cerngoch (English: 'Redcheek'). Ten years after John’s death, in 1904, a clergyman and author David Lewis (whose bardic name was Ap Ceredigion; 'Son of Ceredig'), and Daniel Jenkins, a schoolteacher, collected and published a volume of poetry by Cerncoch, entitled ‘Cerddi Cerncoch’ (Poems of Redcheek). Included also were some poems by Amnon II, along with photographs and 80 pages of genealogical charts and biographical detail of the extended Jenkins family. The book was written almost entirely in Welsh with only a few short contributions in the preface from English writers. A reprint was issued in 1994, with a much longer 33 page preface, written entirely in Welsh and minus the poems of Amnon II.

Joseph had entrusted his diaries to his daughter Elinor and her husband Ebenisar who had stored them in the attic of their home, Tyndomen Farm, near Tregaron. Here they lay, untouched for more than 70 years, until found by Joseph’s great-grandaughter Frances Evans. The diaries comprised a mixture of manufactured, shop-bought books and home-made volumes of loose sheets wrapped in canvas. Many were not in the best condition, having suffered damage from sun, water and mould, and having been nibbled by mice, rats, possums and other small animals. Much of the first five years writings have been lost, with the earliest complete volume that of 1845. The winter of this year was particularly harsh in Wales and Joseph describes many of the poorest inhabitants dying from the cold, with funerals performed during blizzards.

Family members destroyed the dairies from the final four years of his life. There was initial reluctance by some members of the family to preserve the earlier diaries and to have them destroyed, mainly because Joseph had painted some family members in a less than favourable light. However, Frances Evans’s uncle, Joseph’s grandson, Dr William Evans, a cardiologist living in London took an interest and eventually edited the diaries, seeking to have the Australian volumes published. ‘Diary of a Welsh Swagman 1869-1894’ was published simultaneously by MacMillan in the UK and by Sun Books in Melbourne, Australia in 1975. For the most part William Evans simply allowed Joseph Jenkins own words to explain why he acted as he did, with little analysis by himself. When comment is made, however, it is clear that Evans' sympathies lay with Joseph Jenkins (ignoring his heavy drinking, for example) and that he considered his grandmother to be largely at fault for his departure. Immediate and strong interest was shown in Australia and the Victorian Department of Education placed the book on the high school history curriculum three years later.

One interested reader was a Peter Bristow from Mt Eliza in the southern suburbs of Melbourne. While on an unrelated trip to the UK with his wife Lois, Bristow had visited Frances Evans and suggested to her that the Australian portion of the diaries might be better placed in the State Library of Victoria, to which he received a favourable response. On his return to Australia Bristow then contacted the State Library with his news. A further visit to Wales by a member of staff at the Australian High Commission followed and, as a result, the Australian volumes were acquired in their entirety by the State Library of Victoria with an official function taking place at the Library on December 8th to 'welcome' the diaries. Manuscripts for the years 1839-1868 and 1895-1898, the years that Joseph Jenkins lived in Wales, in addition to the shipboard diary of the voyage from Liverpool to Melbourne were donated to the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth, along with the diaries of Joseph's daughter Anne covering the years 1886-1947.

A year following the acquisition by the State Library of Victoria saw publication in Welsh of the first biography of Joseph Jenkins, ‘Rhwng Dau Fyd: Y Swagman O Geredigion’ (‘Between Two Worlds: The Swagman From Ceredigion’) by local author Bethan Phillips. She followed this with a second, more sympathetic portrait of Joseph Jenkins in 2002, this time written in English, ‘Pity The Swagman: The Australian Odyssey of A Victorian Diarist’. Fittingly, the book was launched in the Talbot Hotel in Tregaron where Joseph Jenkins spent much of his time before leaving for Australia and the event was attended by two of his great-granddaughters. A docudrama of his life followed. ‘A Swagman from Wales’ was broadcast in 2003, first in Welsh on S4CTV and then in English on BBC2TV.

Maldon was declared Australia’s first ‘notable town’ by the National Trust in 1966 due to it’s almost intact 19th century commercial centre. Many of the drains and gullies built by Joseph Jenkins can still be seen. In 1994, to mark the centenary of Joseph Jenkins’s departure from the town, the local council erected a water drinking fountain and plaque at the Maldon railway station. The plaque cites his own words:

“Through this diary I am building my own monument”.

Though he had already written his own epitaph in 1876:

"Let my Epitaph run thus Here laid beneath a man in name But short of form, of feat, and fame. Himself."

'Once A Not So Jolly Swagman: The Story Of Joseph Jenkins'. Original images and written content © Gary Hill 2012. All rights reserved. Not in public domain. If you wish to use my work for anything other than legal 'fair use' (i.e., non-profit educational or scholarly research or critique purposes) please contact me for permission first.