The Blood Of The Lads, It Falls Like Rain: Portraits Of The Slain From The Rural Welsh Parish Of Llanfrothen In The First World War

Gary Hill

"Heavy weather, heavy soul, heavy heart. That is an uncomfortable trinity, isn't it?"

(Welsh poet, Hedd Wyn, from a letter home, from the front)

•Part 1: Tales of Discontent and Stupidity•

The Great War of 1914-1918 carries H G Wells’ epithet “the war to end all wars”. Which it would never be. For, as the German philosopher Ernst Jünger, himself a combatant, so perceptively remarked:

"Nothing is ever so terrible that some bold and amusing fellow can't trump it."

It began, as Bismarck had predicted, as “some damn thing in the Balkans”. That “damn thing” was not a military invasion, however, but the machinations of a handful of disgruntled young nationalists that unfolded as a dark comedy. Nineteen year old Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip (an ethnic Serb, though not a Serbian citizen, being born a Bosnian) is blamed to this day but several potential assassins lay in wait in Sarajevo on that fateful morning of June 28th 1914 for the visit of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As the six-car motorcade passed by, the first would-be assassin was unable to throw his hand grenade because he found himself standing immediately in front of a policeman. The second, a student named Nedeljko Čabrinović, also aged nineteen years, managed to lob his grenade but the Archduke’s driver spotted it in mid-air and accelerated. It bounced off the back of the car, landing in the fourth car of the entourage and exploded, seriously injuring two of its occupants as well as several bystanders. Čabrinović then ran off, swallowing an out-of-date potassium cyanide capsule that had lost its potency and, in a scene reminiscent of the silent comedy movies of the day, hurled himself into the 10cm deep River Milijacka where he was unceremoniously hauled out by police.

The Archduke carried on to the town hall where he delivered a speech in which he castigated the Mayor of Sarajevo for such lax security. Then, less than an hour after the assassination attempt, Archduke Ferdinand was en route to the hospital to visit the victims when his driver accidentally turned into the street where Princip and his co-conspirators were hanging out at a cafe, having sauntered away assuming their opportunity was lost. Realising his mistake, the driver reversed the car but the engine stalled. Princip saw his chance, and walked to within 2 metres of the Archduke, resplendent in his Cavalry General’s dress uniform with absurdly high plumed headdress, reminiscent of Jonathan Smith's description of the alpha male of some avian species: "The Cock of Lordly Plume". As is the case with many examples of Darwinian sexual selection, the vain proof of the Archduke’s supposed sexual and social superiority was worn at the expense of being overly conspicuousness to any predator. Princip was therefore in no doubt as to which man was his target. He duly shot him then aimed at General Oskar Potiorek, the military governor of Bosnia, but missed and ended up shooting Ferdinand’s wife Sophie, complementing her husband’s plumage by wearing a ridiculously voluminous dress. Princip too attempted suicide using a weakened cyanide capsule but vomited it back up and was arrested by police as he attempted to shoot himself.

It is, of course, simplistic in the extreme to assume that Princip alone was responsible for the war. He was merely the catalyst that ignited a powder keg that had smouldered across Europe for some years. What followed, however, was no less than a fervent dash by all the major players to reach the pinnacle of the mountain of human stupidity. Historian Christopher Clark sums it up in his book ‘The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914’ (2013):

“The outbreak of war in 1914 is not an Agatha Christie drama at the end of which we will discover the culprit standing over a corpse in the conservatory with a smoking pistol. There is no smoking gun in this story; or, rather, there is one in the hands of every major character.”

Princip and his co-conspirators were inept but lucky. Yet their luck had truly terrible consequences for the ordinary folk of Europe. True, they did ultimately succeed in freeing Bosnia of the shackles of Habsburg rule, and by doing so created a vibrant Serbian nation, yet this came at so high a price that no-one could possibly have envisaged; unquantifiable economic, cultural, social and personal ramifications in every community, large and small, of every country affected by the war. Around 37 million people died. And the deaths came quickly. Within eight weeks of Princip firing his shots 300,000 Austrian-Hungarian soldiers had been killed and another 100,000 taken prisoner. In addition, 260,000 Frenchmen had died. It has been estimated that, at the height of the war, during the Battle of the Somme, from July to November 1916, an incredible seven deaths per second were counted.

By the end of it all, four empires had been brought to their knees, including Britain relinquishing her position as the world’s largest economy to the USA. The political influence of Europe’s royal dynasties was considerably reduced, rigid state socialism came to Russia for seventy years (along with the Cold War), Mussolini’s fascism was to arrive in Italy and, partly because of the crushing ignominy and economic damage brought on by the Treaty of Versailles, Germany and the whole world eventually suffered Hitler, Nazism and the Holocaust.

Unmistakeable consequences can be recognised in even the smallest of European communities. In rural Wales, the relative geographical isolation, the Welsh language, nonconformist Puritanism, relentless poverty and even poetry had traditionally knitted the people together. All this was to change. Some villages saw a large proportion of the males of a whole generation disappear within a few short years, never to return. Their insularity was breached. Young men who had never travelled outside of their local area suddenly found themselves in foreign lands, with different climates, languages, customs and religious and political attitudes. For the first time they had no choice but to look outward onto the world. The inevitable cultural and political effects were recognised before the end of the war. Jack Yates, writing in the ‘Cambrian News’ of April 17th, 1917 asked:

“What are we going to do for the boys after the war? We have not changed, but our boys have changed, and the change in them must be reflected in us. They are roughing it shoulder to shoulder with the free born men of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and have made chums of them. What are we going to do? Are we to keep them or are they going to the Colonies? We in the past have had no use for the development of our social or political life.............every man must have a chance to rise on the ladder of life – caste, clique, and panderings to so-called superior people must be a thing of the past.”

Rarely had the human world observed such enormous disparity between cause and effect. If Princip’s words during his trial, “I am not a criminal because I destroyed that which was evil” did not haunt him before he died in April 1918 of tuberculosis (he was two weeks too young to earn the death penalty; two years afterward Čabrinović died of the same disease), they would surely have haunted him had he lived to old age. Ferdinand’s murder impelled Europe’s leading players to recklessly activate their complex system of mutual defence obligations. Powerful military establishments all, terrified that their neighbours would mobilise first. Only two months earlier, US President Woodrow Wilson’s military adviser and special envoy to Europe Colonel Edward House had bluntly described the political mood in Europe as “militarism run stark mad.” And the irony is that Ferdinand himself actually favoured his government having a conciliatory attitude to the Serbs.

Austro-Hungarian diplomats were quick to blame the Serbian authorities, though there is no evidence their government conspired to kill Archduke Ferdinand, other than the few rogue elements in the military who had provided Princip and his co-conspirators with some arms. It was not long afterward that Oskar von Montlong, press attaché at the Ministry of Foreign affairs initially claimed:

“We have no plans for conquest, we only want to punish the criminals and protect the peace of Europe.”

The Russian Ambassador to Belgrade even telegrammed Moscow to confirm he would be taking his summer vacation as planned as little of importance was happening there. In mere days, however, Vienna started demanded a greatly increased role in the governing of Serbia. Within the following five weeks Russia mobilised its army in order to protect Serbia from the increasingly aggressive Austro-Hungarian diplomatic and military posturing and Germany, in turn, lent support to their Austrian neighbours. Even though Serbia largely capitulated to Austro-Hungarian demands, they invaded nonetheless in what we can now view as a hasty show of pride. The French then fulfilled their Triple Entente Treaty obligations toward Russia, forged due to their shared suspicion of Germany, and no doubt to their having lost the territories of Alsace and Lorraine to them forty-odd years earlier. The French ambassador to Berlin, Jules Cambon, was particularly provocative:

“It is false that in Germany the nation is peaceful and the government is bellicose—the exact opposite is true.”

Even neutral Belgium (and even smaller Luxembourg) were unwillingly dragged into the mire by Germany whose General Ludendorff threatened to, and eventually did “bang on the gates” if they refused to cede access to its troops. And refuse to cede they bravely did; an act which proved to be a propaganda windfall for those in Britain who were eager for war. And so finally, Britain, the third member of the Triple Entente, which pledged to uphold Belgian neutrality, decided to also honour its commitments and declared war on Germany, leading Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey to famously lament:

"..............the lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime."

By the time bullets and bombs were flying, the spat between governments in Belgrade and Vienna was no longer of any importance. With the exception of republican France, however, the war can be characterised not only as a series of international disagreements between governments but more of a family argument that had gotten way out of control. A little more than a decade earlier Britain’s Queen Victoria had died. At her funeral, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II, ludicrously adorned in a suit of shining armour minus any damsels in distress, rode his horse alongside that of his uncle, Victoria’s heir King Edward VII, and his cousin, Tzar Nikolaus II of Russia. Victoria’s eldest daughter was Wilhelm’s mother and her official title referenced both the British and German connection; ‘Kaiserin Friedrich Victoria Adelaide Marie Louise, Princess Royal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland’ while Albert, Victoria’s husband and Wilhelm’s grandfather, was officially known in Germany as Albert Franz August Karl Emanuel von Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha. The extended family were to come together again in London nine years later, in May 1910, to bury Edward VII. This occasion saw nine blood-related kings on horses accompanied by seven queens, followed by five heirs apparent. Then, a little over four years later, each family’s loyal subjects started massacring each other, in somewhat dark satirical fashion, led by a Russian general with a German name, ‘Rennenkampf’, a German general named ‘Francois’, and an English general named French. By the end of the war, Wilhelm was in exile, the Austrian Emperor had abdicated and Nikolaus and his immediate family had been murdered.

It has been argued that, had the monarchies been in a position to flex any real political muscle, the war would not have occurred. This may be so. However, family rifts tend to run deep and long, especially when the family silver is the size of a continent. Wilhelm clearly bore a grudge. In an interview in ‘The Telegraph’ in 1908 he accused “you English” of being “mad, mad, mad as March hares.” His reasoning was that the rapid program of construction of Germany’s modern navy was no threat to his European neighbours. It was solely to counteract Japanese power. Few outside of Germany believed him and a few years later he contradicted himself:

“All the long years of my reign, my colleagues, the Monarchs of Europe, have paid no attention to what I have to say. Soon, with my great Navy to endorse my words, they will be more respectful."

The Kaiser had a reputation for being impulsive and prone to belligerent language but later disclosures from personal correspondences and diaries do bear out his feeling that he had been ostracised by his extended family. Even though he was a personal friend of the murdered Archduke, however, this in no way excuses his childish petulance, his threat of what “my great Navy” might do to innocents. The stark reality is that the political elite as a whole, monarchs, parliamentarians, the military establishments and even newspaper proprietors, displayed a wanton lack of both an understanding of the situation or any heed for ordinary citizens. This is no more evidenced than by the relatively meagre newspaper coverage given in Britain to the murder of Archduke Ferdinand compared with, say, the Tonypandy Riots (1910), the National Railway Strike (1911), the National Coal Strike (1912), or the Dublin Lockout (1913). Indigenous peasants revolting against their rightful masters were always going to be a bigger story for those wielding real political power than the murder of an Eastern European noble many of their readers would never have heard about before.

In possibly the finest novel written in the Welsh language, ‘Traed mewn Cyffion’ (‘Feet in Chains’; 1936), Kate Roberts wrote of the Welsh people’s bafflement:

“When war broke out no-one knew what to make of it.”

For most, their only point of comparison was the Boer War a decade or so earlier; fought by a professional army in an infeasibly distant place, having little or no impact on everyday life in either urban or rural Wales. Roberts’ was describing, as fellow author James Vilares points out:

“............a realist’s Wales, a Wales where wages are low, working conditions poor, worker unity uncommon, food scarce and education scarcer.”

But what excuse could the well-educated, well-paid and full-bellied London intelligentsia proffer for their own ignorance? Incredibly, a day or so later, the London Telegraph's editorial demonstrated that their best political analysts were no more in the loop than Kate Roberts’ hapless Welsh characters:

“..............the circumstances are so peculiar that it is very difficult to understand the reasons for the crime or the exact motives of the murderer” and that the only result would be to “exasperate Teutonic feeling against the Slav nationality.”

This shallow analysis and understatement appears alongside a full page advertisement informing readers somewhat more confidently that it was “a good day if you’re thinking about buying a corset.” How wrong they were. And how wrong and pitiless some of them remain, evidenced a century on by the then Conservative Minister for Education Michael Gove’s ludicrously insensate remark that the present preoccupation with the war as being, in the words of poet Robert Graves (who fought with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers), “monstrous stupidness and futility”, is no more than “left-wing mythology.”

The fact remains that there lacked a single person in any position of power with the insight, courage or will to manage the impending crisis by forging some sort of compromise between either the extended royal family, their governments or both. It seems a classic case of the Dunning-Kruger effect; little ability to perform any credible analyses accompanied by overestimations of military capability, particularly by France and Russia who were late to realise the magnitude of the early German advances (having concocted a plan to overcome most of Europe in as little as 39 days). Military planning was also poor, including the use of 19th century assault tactics in response to German 20th century mechanised firepower and, as we with recent military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq, no thought given to any viable exit strategy. In short, each government had viewed war as a politically expedient opportunity, rather than a catastrophe to be avoided. Certainly, British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and his Cabinet could have chosen to not get involved. But, as they pointed out, was it really feasible to stand back and take the risk that the Germans would capture the ports on the opposite side of the channel from which they could base their navy? Nevertheless, like other governments and their roused citizens, they became deluded by the notion that war would be short-lived and certainly go their way; “Home for Christmas” was the popular slogan. An editorial in the ‘Freethinker’ of August 16th 1914 probably best summed up the mood across Europe:

“................peace at any price is as mad a policy as war at every opportunity.”

•Part 2: Who's War Was It?•

Nowadays the only visible reminder of the First World War in the towns and many of the villages throughout Wales is the war memorial. The rural village of Llanfrothen in the modern county of Gwynedd is no exception. Erected in 1922 it lists the names of the dead who had resided in Llanfrothen Parish, which includes the neighbouring hamlets of Croesor and Rhyd. The Grade II listed monument was designed by Sir Clough Williams-Ellis, a noted and prolific architect and resident of Llanfrothen for most of his life who himself had served in the Welsh Guards and Royal Tank Corps between 1915 and 1918. Best known for his construction of the nearby Italianate village of Portmeirion, the stone memorial, not surprisingly, is more ornate than most. It comprises a square tower whose walls taper inward, culminating in a pyramidal roof with a finial resembling a flaming urn sitting atop. After World War II the names of local men who had given their lives were carved on a slate slab located directly opposite to the inward facing slate plaque which commemorates the First World War dead. The name of Clough’s son, Lieutenant Christopher Williams-Ellis of the Welsh Guards, is carved into the later slate. He was killed in battle at Montecassino, Italy in 1945.

There are seventeen names on the slate plaque concerned with the First World War. They served in all three forces, though the majority were in the army. Arranged in alphabetical order they are, as inscribed:

E Ellis; H D Evans; J O Evans; R R Griffiths; D P Jones; E Jones; H Jones; J O Jones; W Kellow; D Owen; E Owen; O E Owen; S Owen; D M Williams; R D Williams; W D Williams; W R Williams.

Echoing Jack Yates’ newspaper article of 1917, Morfudd Nia Jones, writing on the National Library of Wales website, describes young men like these from rural Wales:

“These were Welsh-speaking, simple, unpretentious working-class boys” now living in “the bigger world they’d been forced to inhabit by the declaration of war.”

Applied to the men from Llanfrothen Parish, she describes all of them (with a single exception) well. They would probably have stood out most noticeably by having English as a second language. Data gleaned from the 1891 census in the administrative district of Ffestiniog, which included Llanfrothen Parish, shows that slightly fewer than 77% reported themselves as monoglot Welsh while fewer than 2.5% could speak only English. These figures are prone to some exaggeration, certainly, as some people are known to have claimed no knowledge of spoken English in an attempt to bolster the standing of the Welsh language. This was undoubtedly intended to counter, among other things, the prevailing attitude in their children’s education to the effect that ‘Englishness’ and fluency in the English language was a cultural norm and failure to grasp this ‘fact’ and act accordingly branded a child as somehow intellectually inferior. There is a plethora of disapproving reports from government inspectors of the day attesting to this view, littered with disapproving comments like “Emrys Jones has the Welsh accent rather strong when speaking English” and “James Hedley Jacob’s accent would be noticeable out of Wales.” As local historian Bob Owen noted, the result was often children more knowledgeable of the geography of the Lake District than their native Snowdonia and of “third rate English poets” than local Welsh poets.

Nevertheless, such subterfuge by parents would have impacted only on the perception of bilingualism; the number of those who considered and used Welsh as their daily first language would have remained unaffected. Whatever the actual situation, it remains the case that twenty years later, in the census of 1911, 37.5% of the population of the county of Meirionethshire (of which Llanfrothen is part) still described themselves as monoglot Welsh speakers. These local statistics were unable to be sustained throughout Wales, however, for the war had a significant effect on the language. Half of the soldiers who enlisted in Wales and later killed were first-language Welsh speakers and so the decade 1911-1921 saw an unparalleled decrease of 15% in the total numbers of Welsh speakers.

Ironically, this loss of first-language Welsh speakers occurred after several decades of a slow but sure appreciation from outside Wales of its distinct cultural and national identity. The first sign of this was probably the passing of the 1881 Welsh Sunday Closing Act, followed by Cardiff attaining city status in 1905. The following year saw the newly elected Liberal government establishing several Welsh-only bodies, including a Department of the Board of Education, the National Council for Wales for Agriculture, and a Welsh Insurance Commission, along with a National Library and National Museum. It is telling, then, that the fledgling modern nationhood of Wales (as well as recognition of the already well established national identities of Scotland and Ireland) was so blithely ignored in some quarters. This is amply illustrated by the very first words to the forward of the document 'The Roll of Honour: A Biographical Record of all members of His Majesties Naval and military Forces Who Have Fallen in the War':

“These men have laid down their lives for England...........”

This is insulting to the memory of those Welshmen who gave their lives. It is likely that few would have seen themselves as risking their lives solely for the good of England. Wales, yes. Britain maybe, but not England alone. The Irish writer Padraig Yeates recounts how his grandfather, on receiving a medal for gallantry, replied to the King's patronising "congratulations, Paddy" with the retort "thanks, Kingy". It was, writes Yeates in his essay 'No Poppy, Please':

"His way of saying he was not fighting for king and country, to save the British Empire or to keep his betters in the manner to which they felt entitled."

Indeed, the decisive factor for some Welshmen (and no doubt some Irishmen) was a sense of kinship with Belgium, another small nation with politically and culturally overpowering neighbours. As local politician Lloyd George declared, the war was one, “fought on behalf of five foot five nations.” Worse, the ‘Roll of Honour’ is scandalously incomplete and its content overwhelmingly English. Only one of those seventeen men from Llanfrothen Parish named on the memorial stone rates a mention; the only one who had achieved an officer’s commission. Not surprisingly, attitudes like this, as well as the influence of some nonconformist preachers, had traditionally led the Welsh to be less than enthusiastic at the idea of serving in a British army dominated by the English. As the poet Robert Graves observed:

“The chapels held soldiering to be sinful and in Merioneth the chapels had the last word.”

In 1913, although the population of Wales constituted 5.4% of the total British population, only 1.8% of the British army were sourced from Wales. Even Welsh regiments were forced to regularly recruit in England, leading to the Royal Welsh Fusiliers being known colloquially as ‘The Royal Birmingham Fusliers’. Although Welsh enlistment picked up at the start of the war, they still lagged behind the rest of Britain; whereas 6.61% of Scottish and 6.04% of English males enlisted within the first month, the figure was 5.83% for Welsh men. The figure for bona fide Welshmen was actually lower; it is estimated that around 20% of the men living in Wales who had voluntarily enlisted at the start of war had been born in England. Nor was this attitude confined to Welshmen living in Wales. In October 1914, the 'South Wales Daily News' reported that plans to raise a separate London Welsh Regiment had to be been abandoned as only half of the necessary one thousand men had enlisted. These were later incorporated into the 15th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. It is ironic, then, that the casualty rate for soldiers from Merionethshire, a region that saw hardly any English immigration compared to South-East Wales, was twice that of the national average.

So, while the events that that began the war are often portrayed as the stuff of high society, recounting tales of prime ministers, aristocrats and generals, the day to day reality of the war itself, of the rank and file fighting soldier; the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker, or, in the case of the men from Llanfrothen, the quarryman and farm worker, was as far as you can get from such opulent fantasy. What follows here, as well as can be pieced together, are the brief lives of ordinary young Welshmen who found themselves, through no particular desire or fault of their own, embedded in situations of extraordinary madness.

William David Williams (1895-1915)

The first man to die with a connection to Llanfrothen Parish was William David Williams. Records indicate that he was born in Llanfrothen in 1895 to Owen and Ellen Williams (née Lloyd) and baptised in Llanfrothen church on June 2nd 1895. A church baptism, while it would hold no particular significance in most European countries, was not the norm for a working class family in Llanfrothen, due to the strong nonconformist religious tradition in Wales. The then Anglican-parented ‘Church in Wales’ (disestablished in 1921) had long been associated with cultural 'Englishness' and 'landlordism' and catered largely to the local English and 'aspiring' Welsh who tended to speak English by choice, even when their own language could be fully understood and fluently spoken. In other words, attending church, rather than a chapel belonging to a nonconformist sect, was often seen as a prime social indicator of influence and wealth or the desire for that influence and wealth. Thus the majority of working class families in Llanfrothen Parish (or indeed most rural Welsh villages) in the early part of the twentieth century did not attend church and did not baptise their children in the church.

Also unusually for the era, William David appears to have been an only child. The war memorial lists the family as having lived at ‘Penstep’, then two separate dwellings and now a single residence. However, mistakes on war memorials are by no means unusual and if indeed he did live there it appears to have been only for a short time. According to the 1901 census the family lived in one of the Plas Brondanw apartments and on that particular night William David was staying with his maternal grandparents David & Anne Lloyd at Pen Y Domen, a nearby cottage. By the time of the next census in 1911 his maternal grandparents (but not his parents), are listed as residing at Penstep, but William David Williams, then aged 16 years, was living and working on a farm named Ty’n Dwr owned by a Jannett Griffith aged 76 years and her daughter, also Jannett, aged 50 years. Then, sometime between 1911 and 1914 William David appears to have shifted to South Wales, either with, or to join his parents, and subsequently lived with them at 23 Penn Street, Treharris, Glamorgan.

It was here that William David Williams volunteered for the army at the start of war, assigned to the 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment (regimental number 12318) where he served as a Private. In September 1940 the War Office repository in Arnside Street, London was badly damaged in a German bombing raid. Over half of enlistment documents, as well as other First World War records were either burnt or heavily damaged by water, including those of William David Williams. There is therefore no enlistment record indicating how he made his living, which might give some clue as to why the family relocated to South Wales. Most likely, however, the move was made to take advantage of the higher wages, and more regular work, as well as the more enticing urban lifestyle available in the South Wales coal producing regions.

Coal was an industry which had undergone an astonishing rate of growth in the previous half century. There were 688 collieries in South Wales in 1910, employing 10% of all the males then residing in Wales and responsible for producing a third of all the coal mined in the world at that time. The requirement for labour caused a 253% increase in population in the county of Glamorgan between 1861 and 1911, a rate of immigration matched only by the United States. The population of the Rhondda Valley alone, for example, had increased from 12,000 to 128,000 in the 30 years following 1861. Comparisons of censuses between1851 to 1911 indicate the impact that the coalfields had on the Welsh demographic; by 1911 more than two-thirds of the total population of Wales lived in either Glamorgan or Monmouthshire. The coalfields were also directly responsible for a massive concurrent increase in urbanisation. In 1851 Wales was an overwhelmingly rural nation with eight in ten of the population resided in rural parishes and small villages, such as Llanfrothen. However, by 1911 this figure had halved and was now considerably less than 50%. Thus the majority of Welsh people, such as the Williams family, were now living in urbanised areas such as Treharris. Indeed, It would surprise many people to know that the proportion of the Welsh population who made their living from agriculture, forestry and fishing in 1911 was as low as 12%.

Another reason for moving from that part of Wales where a large number of the workforce had traditionally been employed in slate-quarrying (in Llanfrothen, by far the majority of men) to a coal mining district might have been the perception that coal mining was a far safer option. The Inspector of Mines for North Wales, Clement La Neve Foster had written in one of his annual reports in the late 1890s that:

"The average death rate from accidents underground is nearly twice as high in the slate mines as in other mines of my district...............as far as safety is concerned it is better to work in a colliery than in an underground slate mine.”

In a paper authored by Dr John Williams in the 1890s, ‘Peryglon i lechyd y Chwarelwr’ (Dangers to the Health of the Quarryman) quantifiable evidence was presented of the dangers inherent in slate quarrying. Between 1883 and 1893 the mean age at death of those employed in the dressing sheds where slate dust was most concentrated was 47.9 years. Those working underground actually digging the slate had the advantage of only a few more months, 48.1 years. In contrast, the mean age of death for those men with least exposure to the dust, such as engine drivers and plate layers, was well above the national average, at 60.3 years.

In the event, William David Williams was not to succumb to a mining disease or a pit disaster in either a slate quarry or coal mine. He was killed in action on May 9th 1915 during the Battle of Aubers Ridge. This joint Franco-British attack was initially planned for several days earlier but heavy rain on May 6th followed by dense mist on May 7th had caused a postponement. May 9th was a sunny, cloudless day. The following extract is from a letter written on the day by Harry Boneham, of Mansfield, England, an infantryman at Aubers, to the landlord of his local pub. It was published in the ‘Mansfield Chronicle' on May 21st 1915:

"Eventually, however, we saw streams of light in the east, followed shortly afterwards by a beautiful sunrise. Skylarks were whistling overhead as gaily as could be, as if there were no such thing as war in the world. What a change in the state of affairs there was a few minutes later though. A single shell came howling through the air from one of our big guns far at the back. This was followed by a regular hurricane of shells from all the guns that had been massed for the attack. The noise was deafening, what with the whizzing overhead and the explosions in front, while the sight behind the German trenches reminded one of a storm at sea, clouds of dust and earth being thrown into the air much as the spray is when waves dash on the rocks"

Official records show the British army suffered 11,619 casualties at Aubers Ridge yet they made no advance on the German line at all; the vast majority fell in the most pointless way imaginable, within a few metres of their front-line trench. By the time the 1st Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment attacked during the afternoon, most of the British losses had already occurred. William David Williams' regiment were no doubt aware of this. One can only imagine the ominous mood that must have prevailed as they climbed out of their trenches with the knowledge that so many of their comrades had already been mowed down by machine guns. That afternoon, twenty-one year old William David Williams fell too, alongside 261 of his regimental colleagues.

Although the use of machine guns was not unknown to any of the European armies, they had previously only been used against the natives of colonial territories and never on European soil. They had, nevertheless, been used with devastating effectiveness. During the Maji-Maji rebellion in German East Africa in 1905, a native spiritual leader named Kinjikitile Ngwale managed to convince thousands of warriors from several tribes that he had cast a spell that would that turn German machine gun bullets into water. Armed only with spears and poison arrows they repeatedly charged a German fortification armed with only two machine guns until all had been slaughtered. Although superstition no longer played any significant role in European warfare, indicative of the short-sightedness of the British (and French and Russian) military establishments was the denial that machine guns would feature largely in any conflict between civilised nations and, even if they were, they would make little difference to the outcome. In common with East African tribal leaders, General Haig had no problem ordering his troops to charge German machine gun nests because he considered the machine gun to be “a much over-rated weapon" that was unlikely to replace an infantry and cavalry armed with rifles and fixed bayonets. His eschewing of technological innovation found support in an officer corps largely sourced by birthright and riddled with outdated notions of colonialism, battlefield heroics and romanticism in which disdain for the welfare of the lower ranks (especially those conscripted) made perfectly good moral sense. In his book ‘A Social History of The Machine Gun’ (1975) John Ellis pulls no punches:

“Of all the chickens that came home to roost and cackle over the dead on the battlefields of the First World War, none was more raucous than the racialism that had somehow assumed that the white man would be invulnerable to those same weapons that had slaughtered natives in their thousands.”

A sentiment echoed by historical writer Eric Byrd in 2014, though rather less floridly:

“The newfangled contraptions might repel a skirt-wearing native with a bone in his nose; but Englishmen [sic] were made of stronger stuff”.

Englishmen, Welshmen, Scotsmen and Irishmen, he surely means. Ellis goes on to describe one case where two German machine guns manned by six soldiers mowed down 600 British infantrymen in two hours without incurring a single casualty themselves. Yet, despite incurring such heavy losses as these, there remained, for some time, a steadfast reluctance to increase the quota of machine guns available to each battalion. In an interview in 1925 General Haig still refused to acknowledge the crucial role the machine gun had played in the devastating early successes of the German forces. It is only fair to mention however that, when the Americans joined the allies, they arrogantly ignored British and French advice regarding the prowess of the German machine gunners, finding themselves as historian Edward Lengel puts it, with fixed their bayonets:

“.........................struggling to cut through belts of wire hung with skeletons in tattered French uniforms”.

General Douglas Haig’s private papers from May 11th 1915 reveal a catalogue of tactical errors including insufficient intelligence about newly-strengthened German positions. Intelligence that had been gleaned was not considered seriously enough. Prior bombardment of the German positions was neither intensive enough nor of sufficient duration to have any real impact and ammunition had been poorly manufactured and equipment often failed due to overuse. The paucity of shells and their high level of failures to explode subsequently became front page news on several national newspapers in Britain with the blame falling squarely on government policy leading to local Welsh politician Lloyd George becoming Minister of Munitions.

William David Williams has no grave. His name is included on the memorial at Le Touret which commemorates, among others, another 13,453 British soldiers killed in this sector of the Western Front between October 1914 and September 1915 whose bodies have yet be recovered.

Daniel Owen (1899-1916)

The Owen family were the hardest hit by the war in Llanfrothen Parish, suffering the loss of three sons within 16 months. Their father John was a quarryman born in 1857 in Llanfrothen. He was probably employed in one of the adjoining Rhosydd or Croesor quarries which were by far the largest employers in the area. John Owen married twice and had eight children by his first marriage, one of whom he lost in the war, and four children by his second marriage to Anne (born 1865), two of whom were lost. The family appear to be unusually mobile for the time, moving house frequently within the parish as well as having individual members relocate to disparate regions of England and Wales. According to the 1881 census John was living with his first wife at Moelwyn Bank in Croesor with their first two children Henry (born 1879; who became a clerk at the Croesor slate quarry, however, by 1916, the year of the family’s first war casualty, he had moved to Liverpool, England) and Owen (born 1880; died in childhood). The couple had three more children within the next decade; David John (born 1884; became a farm worker and living in Yorkshire, England by 1916), Samuel (born 1887; who later moved to South Wales and died in the war) and Kate (born 1889; living in Llandudno Junction by 1916 and believed to have died there in 1974 aged 84 years).

In 1891 the Owen family are listed as living at Siloam Calvinistic Methodist Chapel House, Llanfrothen with a two-month old second daughter Mary (by 1916 she was living at Ty Capel, Bodfean, on the Llŷn Peninsula). A fifth son, also named Owen, was born in 1894 and by 1916 he was also living in Yorkshire. A third daughter, Ellen (known as Nel) was born in 1895. By 1916 she was living in Cardiff where she died in 1922 aged 27 years. Sometime in 1895-6 John married Anne with whom he had four more children within seven years. William (born 1896) became a gardener; Evan (born 1897) became a farm worker and died in the war, as did Daniel (born 1899). Finally, another daughter Olwen was born in 1903, by which time the family were living at London House in Llanfrothen (since renamed Garreg Wen). However, by 1911 and throughout the war they were living at Llys Brothen in what was then Llanfrothen but since ceded to Penrhyndeudraeth.

Farm worker Daniel Owen was the second man from Llanfrothen Parish and the first son of the Owen family to be lost in the war. He was also likely to have been the youngest to die as there is some doubt as to his real age. According to both the war memorial at Llanfrothen and his grave at Fosse in France, he died aged 19 years. However, census data supplied by his family on two separate occasions indicates he was born in 1899 which would make him 17 years old at time of death. It seems unlikely that his parents would mistake the age of their child by two years on two separate occasions and more plausible that he had lied to the military about his age, a not uncommon practice at the time (indeed, the two youngest Welsh soldiers to have died in the war were only 14 years of age; Richard O’Shay of Newport on May 6th 1917 and Reginald George Lewis of Barry on August 6th 1918). Nevertheless, we know that Daniel Owen joined the 7th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in early 1915. In all, four of the men from Llanfrothen Parish who died in the war spent time with the 7th Battalion.

Welsh Fusiliers (use of the modern term ‘Welch’ was uncommon before 1920) wore a unique feature on their uniform; five overlapping black silk ribbons that ran down their backs starting at the neck. They were seven inches (approximately 18cm) long for ordinary ranks and nine inches (approximately 23cm) for officers, a remnant from the days when British soldiers wore pigtails. The Army Board tried to have the regiment remove the ‘flash’, as it was known, on the grounds that the enemy would be able to identify which regiment the soldiers belonged to. However, the story goes that King George V vetoed the plan, stating:

"The enemy will never see the backs of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers.”

This was not really an accurate statement. The battalion embarked for Gallipoli, Turkey on May 19th 1915 from Devonport, England, landing at Suvla Bay on August 9th. There they suffered exceptionally heavy losses unsuccessfully trying to capture Constantinople (now Istanbul), reducing the Battalion to a mere 15% of its normal strength and, of the soldiers remaining, many suffered the effects of disease. They retreated and were initially evacuated on December 11th to the Greek island of Moudros and two months later, in February 1916, the battalion regrouped in Alexandria, Egypt. Their task was to protect the Suez Canal from Turkish attacks coming through the Sinai.

Records show that Daniel was discharged from the army on March 5th 1916, though the reason why is unknown. Perhaps they found out he had lied about his age at enlistment? He was returned to Britain. However, three weeks later, on March 26th, he re-enlisted as a Sapper/Pioneer in the 4th Battalion of the Royal Engineers Special Brigade (regimental number 130586) on ‘short service’ (i.e., for the duration of the war) in Oswestry, England, giving not the address of his parents but a different, Penrhyndeudraeth address, further suggesting that he was lying about his age. He joined his unit on May 9th.

Although the rank of ‘Pioneer’ had existed since the 1700s in the British Army, whole infantry Pioneer Battalions did not exist until 1915. Originally, each infantry company had a ‘Pioneer’ who would go ahead of the company, equipped with an axe, to clear the path through undergrowth. For some reason, they were also the only soldiers permitted to wear a full beard. Pioneer battalions in the First World War had a very different role, i.e., to consolidate and maintain any enemy positions that had been captured. This became necessary during trench warfare because captured German trenches had often been badly damaged and in need of repair and because they now faced the wrong way, having been constructed to accommodate armaments aimed at the British and French lines. Pioneers were armed with both a rifle and a spade (and so wore a badge consisting of a rifle, pick and shovel) and were usually among the first infantrymen to breach the enemy lines. Despite this, fatalities in Pioneer battalions were relatively light compared to combatants. Pioneers had to be extremely fit. According to regulations, each Pioneer was expected to be able to excavate a minimum of 30 cubic feet (8.5 m3) of soil in the first hour.

Daniel was killed in action from gas poisoning on a rain sodden June 28th 1916, a mere three months after re-enlisting and seven weeks after joining his unit. There is a sad irony here; the 4th Battalion of the Royal Engineers being one of the first British units to employ poisonous gas themselves. Nevertheless, even if his military age is the more accurate, it remains that he had experienced two of the most horrifying theatres of war during his teenage years, Gallipoli and the Western Front. His body is buried at Fosse No.10 Communal Cemetery Extension, Sains-en-Gohelle, Pas-de-Calais, France which harbours 471 graves, 256 of which are British.

Samuel Owen (1887-1917)

The eighth Llanfrothen parishioner and second son of the Owen family to die was Samuel. Little is known about his life. He appears to have moved to Ferndale in South Wales perhaps, as William David Williams is suspected, to work in the coal mining industry. He then enlisted at Porth, Glamorgan, sometime after December 1915, possibly in March 1916, serving as a Sapper (or military engineer) in the 250th Tunnelling Company of the Royal Engineers (regimental number 155488).

Their aim of these companies was to burrow underneath the German trenches and to place mines directly underneath and in the path of their advance. In order to excavate tunnels more quickly and safely, the British Army prioritised the voluntary enlistment of experienced coal and tin miners, especially in South Wales, who were used to working underground under cramped conditions, many since childhood. By mid-1916 25,000 experienced miners had enlisted, the majority coming from coal mining communities. Some had previously been rejected for combat roles on the grounds of health and age. The work was highly dangerous with numerous risks including tunnel collapse, carbon monoxide poisoning, inadvertent detonation of their mines, being discovered by the enemy and either gassed or forced into combat underground. In addition, the presence of tunnelling companies was disliked by above ground infantrymen because when tunnelling was suspected, it increased the chance of aerial bombardment. There was also the added risk of accidental detonation of explosives underneath friendly forces and, even when controlled explosions were successful, they would randomly shower the air with shrapnel, an event which favoured neither allied nor enemy forces.

The 250th Tunnelling Company was formed in Rouen, France in October 1915 and, in collaboration with a larger contingent of similar tunnelling units from New Zealand and a smaller contingent from Australia, they constructed three tunnels under the Messine Ridge in Belgium (up to 38 metres deep and 600metres long, packed with 435 tonnes of explosives) which they named Petit Bois, Peckham and the largest, Spanbroekmolen. This is now considered the greatest achievement of the allied tunnelling companies. At 3.10am on June 7th 1917 the explosives were detonated creating a noise so powerful it registered on a seismograph in Switzerland, and was heard by David Lloyd George, 240 km away in London. Over 10,000 German troops were killed outright and the German positions were overran by the British in three hours, with a further 7,000 Germans taken prisoner.

Thirty year old Samuel Owen died on June 23rd 1917 almost a year after his half-brother Daniel. He had succumbed to the wounds he had suffered three weeks earlier on June 6th, one day before the excavations he helped construct were detonated. His body is buried at Bailleul Communal Cemetery Extension in Northern France along with 4,236 other war graves of which 3,292 are British. The 'Register of Soldier's Effects' refers to his next of kin as his wife, Jane, but this may be mistaken as there appears to be no record of him ever marrying, either in North or South Wales.

Evan Owen (1897-1917)

The ninth member of the Llanfrothen community and the third son of the Owen family to die was Evan, also a farm worker. He was a full sibling to Daniel and a half-sibling to Samuel. Unlike his two brothers Daniel was not in the army but served as a Royal Navy Stoker 2nd Class, (naval number #K43043) aboard HMS Brisk, an Acorn (H) Class Destroyer/Torpedo Boat Lieutenant captained by Lieutenant Algernon Edmund Lyons (a fellow Welshman born at Kilvrough, near Swansea, Wales; after 1922 he became known as Penrice-Lyons) and launched in 1910 at Clydebank in Scotland.

During his time afloat Evan Owen can be proud to have played an honourable role in what is considered to be one of the most distasteful and disgraceful episodes in a war which was short on neither. The story involved a collision between two ships, the SS Darro and the SS Mendi, early morning on February 21st 1917, 11.3 nautical miles south to southwest of Catherine’s Point on the Isle of Wight. The SS Darro was a cargo ship of slightly less than 10,000 tonnes which regularly carried foodstuffs and mail between Argentina and Britain. After berthing at Le Havre, France, it was bound for Falmouth, England with a cargo of frozen meat and a crew of 143 under the captaincy of Henry Winchester Stump. The SS Mendi was a much smaller steamship of less than 4,000 tonnes owned by the British and African Steam Navigation Company. It normally plied between Liverpool and West Africa (being named after a tribal group in Sierra Leone) but had been chartered by the British government a few months earlier to ferry troops. Captained by Henry Arthur Yardley the SS Mendi was en route from Plymouth, England to Le Havre carrying 969 people; 802 volunteers from the South African Native Labour Contingent (SANLC) who had boarded at Cape Town 38 days earlier (most of whom had never been on a ship of any kind before), five officers, 17 non-commissioned officers and 56 other military officials. A crew of 89 were also aboard.

Because of the threat posed by German naval ships and submarines both ships took protective measures; SS Mendi was shadowed by HMS Brisk while the SS Darro sailed an unpredictable zig-zag course. Conditions were very foggy and visibility poor so the SS Mendi and HMS Brisk travelled very slowly, the two ships not always visible to each other, with the SS Mendi sounding its horn at one minute intervals in line with maritime regulations. In contrast, and with complete disregard to regulations, the SS Darro was travelling at its full speed without sounding its horn. At 4.57am the lookout on the SS Mendi, Fourth Officer Hubert Frank Trapnell, spotted the SS Darro at a distance of only 60 metres travelling on a collision course to starboard, making no attempt to either slow down or alter course. Second Officer H. Raine immediately ordered the ship full astern but it was too late. The SS Darro hit the SS Mendi almost at right angles causing a six metre tall vertical gash from keel to deck. Worse, the bulkhead separating numbers 1 and 2 holds was ruptured causing icy-cold water to flood into an area where an estimated 140 SANLC volunteers were sleeping, drowning them all instantly. The Mendi was pushed over sideways, submerging all the lifeboats on one side though, incredibly, it transpired later that there were only ever enough places in the ship’s complement of lifeboats for 298 people. The SS Mendi took less than 30 minutes to sink completely. Those remaining alive found themselves in icy water with visibility reduced to only a couple of metres. Of the 649 who perished, 626 were SANLC volunteers, the majority unable to swim.

The SANLC members had not volunteered to fight as infantrymen because they were not allowed to. It was a stipulation of the South African government that only white South African volunteers be trained in the use of firearms and explosives, lest any black volunteers later use their military skills to overthrow the government. Instead, they were expected to support the war effort by working in quarries, cutting timber, building and repairing roads and railway lines and loading and unloading munitions and supplies from ships.

Although they were not allowed to bear arms, this did not mean SANLC volunteers did not serve on the battlefield. The British cemetery at Arques-la-Bataille, France, for example, includes the graves of 333 SANLC volunteers who were killed in battle, unarmed. On their return to South Africa white volunteers were awarded medals and given parcels of farmland from which they could make a living and build a government subsidised home. Black volunteers, despite similar experiences and sacrifices, were rewarded with no medals and no land, but were each given a bicycle for which, no doubt, they were expected to be grateful. One can only look back with hindsight and dismay as to the short-sightedness of the South African government. For, had they been allowed to serve alongside their white colleagues, there is little doubt that the SANLC volunteers would have fought with the same degree of bravery. This view is borne out by eyewitness reports from the crew of the HMS Brisk and other ships nearby that came to render aid to the SS Mendi. At the subsequent Maritime Board of Inquiry they spoke unanimously of the bravery and courage of the surviving SANLC volunteers in helping the rescue efforts.

Their African-American counterparts, such as those of the 369th New York Infantry, fared little better. Many had volunteered from the Deep South in an effort to prove their worth as loyal citizens, on the understanding that measures would be put in place on their return to improve their lot in the social hierarchy. However, on arrival in Europe they soon found themselves unattached from US forces and put under French command. They too demonstrated their bravery. Unlike the SANLC men they were armed and their unit recaptured the French town of Sechault from the Germans, only to find themselves cut off from the allies by German forces. Though low on food and ammunition, they nevertheless managed to remain fighting for a whole week, holding onto the town, until help arrived, earning them the nicknames ‘The Harlem Hellfighters’ and ‘The Lost Battalion’. For their service to France the government awarded every member of the regiment the Croix de Guerre and it is said that in return, French culture absorbed the jazz that they had played for recreation. It seems the French definitely got the best deal.

In all, more than four million non-white soldiers fought for the allies in the war; one and a half million came from the Indian subcontinent and two million were recruited from the various British and French African colonies. Indian battalions played a particularly pivotal role in all the Middle Eastern theatres. It is easy to forget, then, that a Hindu Indian from the tropical south of the country fighting in the Egyptian desert would be just as much out of their geographical and cultural depth as would a Welshman from Merionethshire. The multiracial nature of the British and French forces was in stark contrast to the opposing Germans, so much so that the German sociologist Max Weber disparaged them as comprised of “niggers, Gurkhas, and the barbarians of the world.” Nevertheless, there was some unease in Britain about the presence of non-European soldiers because, paradoxically, the success of the war effort depended to no small extent on the effectiveness of non-white soldiers in killing white Europeans, thus upsetting the strict racial hierarchies on which the Empire was built.

HMS Brisk was the first ship upon the scene of the collision and immediately lowered all of its lifeboats, rescuing 137 of the Mendi’s passengers and crew from the water, without regard to race. Similarly, the nearby cargo ship SS Sandsend managed to pick up 23 black survivors (and later to lose 3 men itself after being torpedoed off Cork, Ireland the following September). But this is what renders the event distasteful and disgraceful: not just the wanton stupidity of the SS Darro having ignored maritime regulations and causing such a catastrophe, but the fact that having ascertained that they had suffered only minor damage themselves Captain Stump callously ignored the fate of the Mendi and immediately steamed away from the scene. No attempt was made to communicate with the stricken vessel and Captain Stump waited a full three minutes before informing HMS Brisk that it was his ship that had collided with the SS Mendi. The SS Darro released none of its own lifeboats but two lifeboats from the SS Mendi made it to the SS Darro. The first, filled with white officers and crew, arrived at about 5.50am. This was the only rescue the SS Darro made. When the second lifeboat, filled with SANLC volunteers, pulled alongside ten minutes later Captain Stump ordered the crew to ignore their cries for help. At 6.45am the SS Darro continued on her way to Falmouth at a reduced speed with her horn sounding while HMS Brisk had her lifeboats continue the search for survivors until 9.00am before having them return, though the ship continued to cruise the area afterward for several more hours.

Two reasons as to why Captain Stump acted as he did have been suggested. The first is that he panicked. This seems unlikely, as he must surely have been aware that he would be unable to cover up a disaster of this magnitude, witnessed by a Royal Navy destroyer and a merchant vessel. And it does not explain why he didn’t come to his senses and return to the scene of the collision to help with the search for survivors. The second, suggested by a number of people, including those who knew Stump personally, was that he and his officers would have been uncomfortable having black men on board their ship, regardless of the circumstances. Whichever the case, a Board of Enquiry identified Captain Stump as being wholly responsible for the collision. He was punished by having his Captain’s licence suspended for one year. The families of the SANLC volunteers received no formal notification as to how their relatives had died, or any monetary compensation. Not even an apology from the company that operated the SS Darro.

After their exemplary actions in the rescue of the SS Mendi survivors it seems distinctly unjust that only eight months later HMS Brisk was to experience a similar fateful event. On October 2nd 1917, German submarine U-79, a relatively new vessel displacing 759 tonnes and carrying a crew of thirty-two, was patrolling the waters and laying mines around Rathlin Island off the coast of Northern Ireland. Their goal was to hinder the passage of merchant conveys from the USA to Britain. The sea was calm, Kapitänleutnant Otto Rohrbeck (who coincidentally had taken command of U-79 on the same day the SS Mendi was sunk) reporting in his log a “light westerly breeze is lifting early morning mist over calm waters.” Convoy HH24, inbound from the USA loaded with cotton, alcohol and steel, was being escorted by HMS Brisk and HMS Drake, a 14,000 tonne armoured cruiser captained by S. H. Radcliffe and one of the fastest cruisers in the world at that time. As the convoy steamed past the north-west tip of the island, U-79 sighted HMS Drake and fired one of her four 50cm torpedoes, managing a direct hit. The resulting explosion killed 19 seamen outright though the ship remained afloat. The entire convey then dispersed, as was normal practice in order to reduce the possibility of two ships being hit in quick succession. Soon afterward, however, U-79 either fired another torpedo at the 1,815 tonne merchant ship S.S. Lugano, or it had hit one of U-79’s mines, ripping a large hole in her starboard side. She sank rapidly, though no lives were lost.

Torpedoing an armoured cruiser and sinking a merchant ship on the same morning would have been a notable occasion even for a successful naval officer such as Kapitänleutnant Rohrbeck who, within the sixteen months he commanded U-boats, sunk a total of 11 ships and damaged two others. There is some doubt, therefore, whether the third explosion that subsequently ripped the bow off HMS Brisk 1.5 nautical miles south-west of Bull Point, County Antrim, was due to a mine laid by or a torpedo fired from U-79. A mine is considered by most experts to have been the cause. Surely few captains would have been lucky enough to torpedo one of the fastest cruisers in the world, a modern destroyer and a merchant ship within a few hours? Whatever the case, 32 of the crew of HMS Brisk died; 31 instantly and one critically injured, who died within a month. Twenty-year old Evan Owen of Llanfrothen was one of those who died instantly, alongside his local Welsh compatriot William Ewart Williams from Caernarfon. Evan Owen’s body was never recovered and, in addition to the Llanfrothen war memorial, he is commemorated at the Plymouth Naval Memorial.

As reported in the next edition of the Rathlin Island newspaper:

“...the islanders watching all this in amazement from the cliffs and the settlement at Church Bay, the mutilated silhouette of the Brisk was being approached by two of the many armed trawlers on hire to the Admiralty, ‘Seaton’ and ‘Vale of Lennox’.”

The stern section of HMS Brisk was towed into Derry. She was repaired and continued service until 1921 when she was scrapped. U-79 sank only one more ship after the encounter off the Northern Ireland coast. A mine she laid sank a smaller 205 tonne ship three weeks later. On November 21st 1918 she was surrendered to the allies at Harwich, England and given to the French Navy who renamed her Victor Reveille. She too was scrapped, in 1935.

Elias Jones (1890-1916)

This family lost two sons 27 months apart. They lived at three separate addresses in Rhyd over a forty-eight year period. According to the 1881 census they were living at Ty Talcen. In 1901 they resided at 1 Tanymarian, and then moved to Brynhyfryd sometime before 1911 where their mother Alice remained until she died. The father, Elias, was born in 1832 in Llanfrothen and worked as a quarryman. He died sometime in the 1890s. Alice, who worked as a housekeeper, was born in 1850 in Llanfrothen and died in 1929 aged 78 years and buried at Ramoth Baptist cemetery. Elias and Alice had seven children together, all of whom were boys. In addition, Elias Jones had a son who died aged four years following his birth in 1872. He is also buried at Ramoth. His mother is listed as an M. Jones. The family also adopted a daughter. In order of birth the children were: John (1872-1876); John Parry (1876-1944; originally a quarryman, later becoming a postman); Owen John (1878-1952), Richard (born 1886 and died before 1891); David Parry (1886-1918; died in the war); Thomas (known as Tommy; born 1888, a quarryman); Elias (1890-1916; died in the war); Robert (1892-1962; quarryman); Lizzie Ellen Hughes (born 1901; adopted).

Elias was the Jones family’s first son to die in the war and the fourth man from Llanfrothen. A quarryman, he enlisted at Penrhyndeudraeth and served as a Private in the 7th Battalion ‘D’ Company, Royal Welsh Fusiliers (regimental number 4325) serving alongside his fellow parishioner Daniel Owen, at Gallipoli. Unfortunately for Elias the 7th Battalion’s presence in Egypt coincided with an unusually severe heat wave; from mid-June to the end of July temperatures as high as 51 degrees Celsius were recorded and large numbers of men became infected with dysentery (Daniel Owen had missed this combination of heat and disease, as he was now serving on the Western Front). This is how Elias Jones died on August 5th 1916, aged 26 years, lying in a hospital bed as his battalion was successfully fighting in the Battle of Romani alongside Australians and New Zealanders facing Turkish troops under German command. He was buried in Port Said War Cemetery in Northern Egypt. The sole newspaper report of his death referred to him as ‘Ellis Jones’.

David Parry Jones (1886-1918)

David Parry was the brother of Elias Jones and the 14th man to die from Llanfrothen. He enlisted at Bala and served initially with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers (regimental number 49703). He was then transferred to 814th Area Employment Company, Labour (regimental number 359152). Unlike the SANLC volunteers, British Labour Companies grew from the Non-Combatant Corps, which were made up of conscientious objectors to the war who, although not willing to bear arms, were nevertheless prepared to do work such as building and maintaining roads and buildings, sanitary duties and handling of supplies. Because there were not enough conscientious objectors to complete all the tasks, dedicated Labour Companies were formed in January 1917 and manned by officers and other ranks who did not meet the medical requirements for front line service such as those who had been wounded. They often worked alongside SANLC volunteers as well as other non-British labour and even German prisoners of war. British members were, however, occasionally used as emergency infantrymen. Not surprisingly for such a bloody and highly mechanised war, by the end of hostilities the Labour Companies represented more than 10% of all men serving in the British Army.

It seems highly likely, therefore, that the reason David Parry was transferred to the Labour Company was because he had been wounded while serving with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers. No dates are available but possibly it was at the Battle of Loos in 1915 or the Battles of Albert or Bazentin in 1916. David Parry arrived in Egypt six weeks before his brother Elias and their neighbour Daniel Owen and remained serving there until his own death, aged 32 years, on November 1st 1918, also from dysentery. It was a mere eleven days before Germany formally surrendered. In honour of the fact that the majority of the men in the Labour Companies had already been injured in combat, those who died while serving are further commemorated as full members of their original regiment. He was buried as such in Cairo Memorial Cemetery.

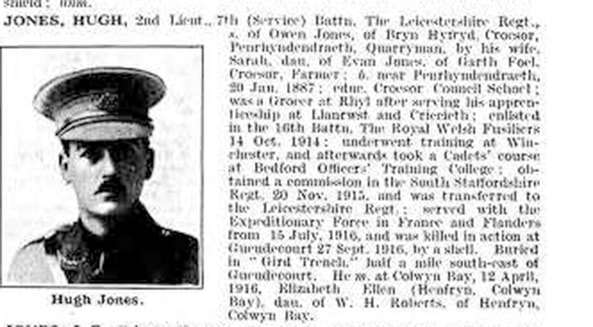

Hugh Jones (1887-1916)

This particular Jones family were residing at 2 Brynhyfryd, Croesor at the time of the censuses of 1891, 1901 and 1911 but sometime after that moved to 2 Park Road, Penrhyndeudraeth. The father, Owen Jones, was not local, being born at Bryncroes, Aberdaron in 1852. He worked as a quarryman and died aged 77 years in 1929. The mother was, however, local. She was Sarah (née Jones) born in Llanfrothen in 1855 and the sister of the essayist Daniel Jones (whose pen name was Daniel Garth Foel) of Ruthin, formerly a quarryman at Rhosydd himself, who won thirteen prizes at separate Eisteddfodau. Sarah died in 1927 aged 72 years.

There were six children from the marriage. The oldest, Catherine, was born in 1882 and died in 1955 aged 73 years. Next born was Evan (1885-1967). The third child was Hugh, born in 1887, who died in the war. Fourth was Daniel, also a quarryman born 1890 and died 1959. John Owen was born 1893 and also died in the war. Finally, Maggie was born in 1895. She appears to have taken after her uncle as a writer. A newspaper report tells us she received equal 1st prize for her englyn in the Eisteddfod Y Plant held in March 1914.

Hugh Jones was the first of the two sons to die and the fourth man from Llanfrothen Parish. In terms of an army career, Hugh was the most successful. He attended Croesor Council School then left to become a servant to Evan and Anne Jones, farmers at Glasdraeth. He apparently undertook an apprenticeship (trade unknown) at Llanrwst and Criccieth and then relocated to Rhyl for a short time on completion. For eight years he was employed by a J.R. Pritchard at the Maypole Dairy Company in Caernarfon where he was also a member of Beulah Calvinistic Methodist Chapel.

Initially enlisting in the 14th (though some sources say 16th) Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in Llandudno during October 1914, he underwent his initial training at Winchester, England and must have shown aptitude for he was immediately accepted as an Officer Cadet at Bedford Officer’s Training College. He obtained his commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 11th Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment in November 1915. He was then seconded to the 7th Service Battalion, Royal Leicestershire Regiment, colloquially known as the ‘Tigers’ because their cap badge displayed an image of a Bengal tiger in honour of the regiment’s prior service in India. A working class Welshman from a small village in North Wales would have stood out in the army of his day for it was an army that, at the officer level, was becoming increasingly dominated by the upper class. In 1875 half of all British Army officers were sourced either from the aristocracy (18%), or the landed gentry (32%). By 1912, however, that figure was closer to two-thirds of officers (24% and 40% respectively).

The only casualty from Llanfrothen Parish we can be certain was married, Hugh Jones wed Elizabeth Ellen Roberts of Henfryn, Grove Park West, Colwyn Bay on April 12th 1916 at Colwyn Bay. Shortly afterward he was shipped to France and fought in the joint British-French-New Zealand-Canadian offensive that became known as the Battle of Morval, one of the Battles of the Somme, designed to take the northern French village of Gueudecourt from the Germans. It was only the second time that tanks had been used in war. Although the offensive proved successful and the village was captured, this was the place where Hugh Jones fell, aged 29 years, killed by a shell on the overcast, rainy day of September 27th 1916. He had been married for less than six months. He was buried in the ‘Gird Trench’, 1 km south-east from where he died. A brief obituary with portrait appeared in the ‘Herald Cymraeg’ on Tuesday October 10th, 1916 and he was the only deceased from Llanfrothen Parish to appear in the ‘Roll of Honour’ (image below). He was also one of only two deceased to have made a will, leaving an estate valued at £57 to his widow (approximately £4,200 today).

John Owen Jones (1893-1917)

Hugh’s brother, John Owen was the 13th Llanfrothen parishioner to die. Little is known of him. It appears he moved to Pwllheli where he worked as a shop assistant in a draper’s shop, ‘Druid House’ (now ‘Pollecoff’s’, a woman’s clothing store) and it was here that he enlisted as a Private in the 7th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (regimental number 291467). He served in Egypt, and was killed in action there (though some sources state Gaza) on March 26th 1917, aged 25 years. As Gaza was then considered part of Egypt, it is feasible that he did die there, which would account for his inclusion on the Jerusalem War Memorial. His body was never recovered.

John Jones was the fourth Llanfrothen parishioner to die in the Egyptian/Middle Eastern theatre; surely none would have predicted this when they were at school. Egypt would probably have been no more than some exotic patch of pink on the schoolroom map of the world, where pyramids and camels existed. A brief obituary in ‘Yr Udgorn’ on February 6th, 1918 (surprisingly, almost a year after his death) described John Owen in strangely religious terms as “humble”, “pure and chaste” and “much beloved by society”.

Richard Rowland Griffiths (aka Risiart Penygraig; 1893-1917)

The fifth family to lose a son was the Griffiths family of Croesor. Another large family, they were residing at Croesor Bach in 1901 but by 1911 they had moved to Pen-y-Graig where they remained for at least the duration of the war. John R. Griffiths was his father, born in the nearby village of Beddgelert in 1869, and dying in 1943 at 73 years of age. He was a quarryman. His mother Catherine (née Roberts) was born in Penrhyndeudraeth in 1872 and died in 1924 aged 52 years. They had ten children in total and although they only lost one to the war this family were particularly unfortunate as they had already lost three others in childhood and another died in adulthood two years before the death of the father.

Their first child, Anne was born 1891. It is believed that she married a Clynnog man, Hugh Roberts, and they farmed ‘Tylyrni’ at Nantmor, near Beddgelert. The second child was born in 1893; this was Richard Rowland, the son who died in the war. The third child, Mary was also born in 1893 and died sometime between 1901 and 1911. Rowland was born in 1895. Next, Kate was born in 1899 but she too died between 1901 and 1911. John was born in 1900, Maggie in 1904 and Jane in 1906. William Morris was born 1910 and died aged 31 years in 1941. The last child, Robert, was born in 1913 and lived for only three months.

After leaving school Richard Rowland Griffiths worked as a quarryman then, in 1910 aged 17 years, he moved to South Wales to work in the coalfields. There he lodged with another coal miner, Evan Jones, at 54 Wyndham Street, Porth while working for the Insole Company, most likely at their Cymmer Colliery at Porth. The Insole family, who had originated in Worcester, England grew to be probably the wealthiest family in Wales at the time with extensive interests in coal and rail. After three years down the mines Richard Rowland enlisted in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers as a Private on March 3rd 1913 at Pontypridd aged 20 years and 4 months, making him the only one of the Llanfrothen deceased who was a regular member of the army at the time Britain declared war on Germany on August 4th 1914. Because his enlistment papers survived the bombing at the Record Office in London in 1941 (the burnt edges of each page are plainly visible on the scans), we know that he was a Methodist with a 2 inch (5 cm) scar on his left buttock. Interestingly, when listing his immediate family members he makes no mention of his siblings John, Maggie or Jane, even though they were all living at the time.

Richard Rowland Griffiths spent the bulk of his army career serving as a Private in the 14th Battalion 'D' Company of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers after their formation in Llandudno in November 1914 (regimental number 10931). He first landed in France in December 1915. In July 1916 they saw action at the Battle of Albert at Mametz Wood on The Somme, where the battalion suffered such severe losses facing German Maxim machine gunners (ironically a weapon invented by an American of German descent) that the regiment was unable to return to any major battle for more than a year. The loss was immortalised by the poem ‘Mametz Wood’ by Welsh poet Owen Sheers from his anthology ‘Skirrid Hill’ (2005; which won the Somerset Maugham Award). Here is an extract:

For years afterward the farmers found them

The wasted young, turning up under their plough blades

As they tended the land back into itself

After the regrouping of the 14th Battalion, Richard Rowland Griffiths found himself in Belgium. There he was killed in action in the region of Ypres aged 24 years. He had been promoted to Lance-Corporal only a few weeks earlier. His body was recovered and is buried at Bard Cottage Cemetery, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium, three kilometres to the north of Ypres, which contains 1600 graves, 1583 of which are British.

On February 5th 1917 in 'Yr Herald Gymraeg', the bard 'Carneddog' published a poem in honour of Richard Rowland Griffiths. Carneddog shared almost the same name (Richard Griffith) as Richard Rowland Griffiths and he was a similar age to John and Catherine Griffiths. Like them too, Carneddog and his wife Catrin had already lost four (of their six) children, the first in 1890. The single verse poem, entitled ‘Nid a’n Anghof’, reads:

Caredig, dewr, a ffyddlon,

A Ffeflyn oedd ‘n y Cwm.

A hiraeth am y gwron,

Fud sanga’r fro yn drwm;

Fe garai cwm ei febyd.

A hoffai pawb ‘n y fro,

Cymwynas lanwai’i fywyd.

A ffrynd i bawb oedd o,

Fe garai hedd y bryniau.

A’i mwyn awelon pur,

Fe’i magwyd are u llethrau.

O swn rhyfelgar gur,

Ond corn y gad adseiniodd,

Un dydd dros fryniau’i hedd.

A’Risiad a’i atebodd,

Ymladdodd hyd ei fedd,

Er cadw’n gwlad a’i breintiau

Ei fywyd ieuanc mad,

O’i wirfodd dan ei arfau.

A roddodd yn y gad

A hiraedd sydd yn cwydro,

I Ffrainc dros donnau’r aig,

Can’s gyfaill “nad a’n ango”

Oedd Risiad Penygraig.

Distawa rhu magnelau,

Fe beidia tinc y cledd.

Ond hiraeth ein calonau,

A bery hyd y bedd:

Tra Moelwyn yn y cread.

Tra môr yn ffurfio’i aig,

Bydd hiraeth pur am Risiad,

Ar aelwyd Penygraig.

I faes y gwaed yn Ypres,

Gwahoddaf natur dlos,

I harddu, er yr ormes.

Ei feddrod gyda rhos,

Ac onid tawel dystio

A wnant wrth fyd di-hedd

Fod rhosyn tlysach yno

Ers deuddeg mis yn y bedd.

Robert David Williams (1898-1917?)

Unfortunately, at the time of writing, the story of this soldier remains uncertain. The Williams family are listed as living at Pen Parc in 1901 and at one of the Plas Brondanw apartments in 1911. They were still living there in 1916. On the war memorial, however, Robert David is listed as living at Penstep. This is certainly incorrect; there is no evidence he ever lived there. The family consisted of the father, William Robert Williams born 1865 in Llandecwyn (though his family were originally from Llanfrothen). He was a quarryman. The mother Alice (née Jones) was born in 1859 in Beddgelert. They married in 1890 and had four children. Edward was born in 1892. Initially a quarryman, he fought in the war as a Private/Gunner in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He too was involved in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. It was from there, in November 1916, he posted a letter home to Griffith Roberts of Traean, Llanfrothen, a portion of which was subsequently published in ‘Yr Herald Gymraeg’. Two months later he was hospitalised in Malta suffering from the effects of exposure. Alice was the next born in 1895. She married Rees Lewis (1882-1962) and initially lived in Ruthin. They then moved to London and in 1923 resided at Arden Road, Finchley. In 1962 she moved again, to Barnes, Hertfordshire. Robert David was born 1898 and Sarah in 1900.