The Dark Ages: Christian Imagery, Atheist Interpretation

Gary Hill

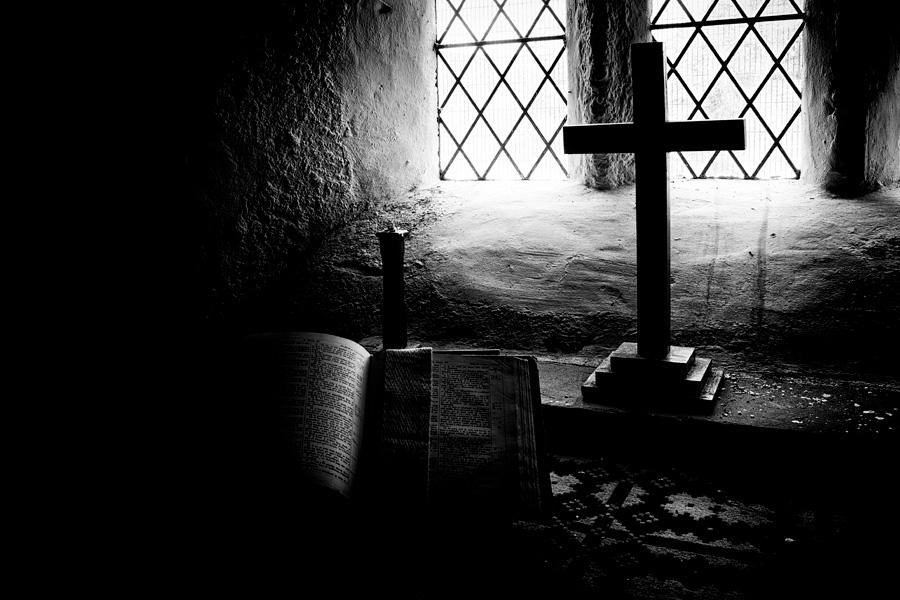

In addition to Veronica, patron saint of photographers (and, apparently, laundry workers), photography and Christianity share two important concepts, that of light and darkness.

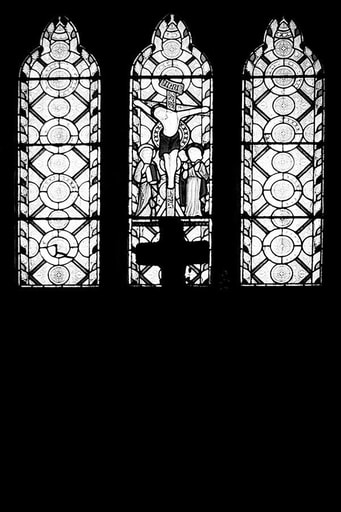

In Christian symbolism, darkness reliably conveys the notion of evil, death and the unknown. In contrast, light conveys only positive aspects such as life, goodness and hope. For example, Genesis tells us that God not only created light, he also saw that it was good. The New Testament describes Jesus as the light of the world and the visionary revelations of John depict Heaven in terms of light. The medieval use of coloured and stained glass within European churches is probably the best physical example of Christianity symbolising the goodness of light; as if the colourful light of the heavens floods the interior of the otherwise dark church with goodness. Although it appears as if Christian symbolism deals with light and darkness in rigid ways this is not always so. Some sects of Christianity view evil and good, not as polar opposites, but in relative terms, evil being the relative absence of good.

This is not unlike how photographers see things. A dark scene can be illuminated but an illuminated scene is not made darker by adding darkness, only by reducing the amount of light. An underexposed scene can often be post-processed to reveal physical features but a grossly overexposed, blown-out scene has lost all such features to the light. Thus to the photographer, darkness is not a thing in itself, either physically or symbolically, but a relative, and eminently measurable, degree of light. And, of course, photography cannot exist without some light, for without at least some photons hitting film or sensor, no image is captured.

Thus to the photographer, darkness is not a thing in itself, either physically or symbolically, but a relative, and eminently measurable, degree of light. And, of course, photography cannot exist without some light, for without at least some photons hitting film or sensor, no image is captured.

Photographers are able to manipulate the light and darkness in a scene in two ways. First, symbolically, they might purposely include a large amount of darkness within the frame (labelled, fittingly, as negative space) to convey the notions of evil, trepidation, unknown, horror etc. Second, they might also include negative space or relative darkness simply as a means of diverting attention to the subject of their image.

As an atheist, I view Christian imagery and iconography wholly as depictions of mythology and consider them to convey stories and ideas and perhaps some abstract or metaphorical truths, but not necessary literal truths. This gives me much to play with in terms of interpreting the imagery as photography because I feel no onus to deal with the symbolism according to tradition, or to present Christian imagery in the ‘right light’. Consequently, although I freely use Christian imagery concerning itself with death, I do not naturally equate the symbolic use of darkness with evil. Rather, I sense solitude and calmness, ignorance, or the unknown, all of which are able to be dispelled by the light.

'The Dark Ages: Christian Imagery, Atheist Interpretation'. Original images and written content © Gary Hill 2023. All rights reserved. Not in public domain. If you wish to use my work for anything other than legal 'fair use' (i.e., non-profit educational or scholarly research or critique purposes) please contact me for permission first.